Poland from Berlin: Wrocław in a Weekend

You might never notice walking around Berlin, but a vast and complicated land lies just over 50 km from the city edge.

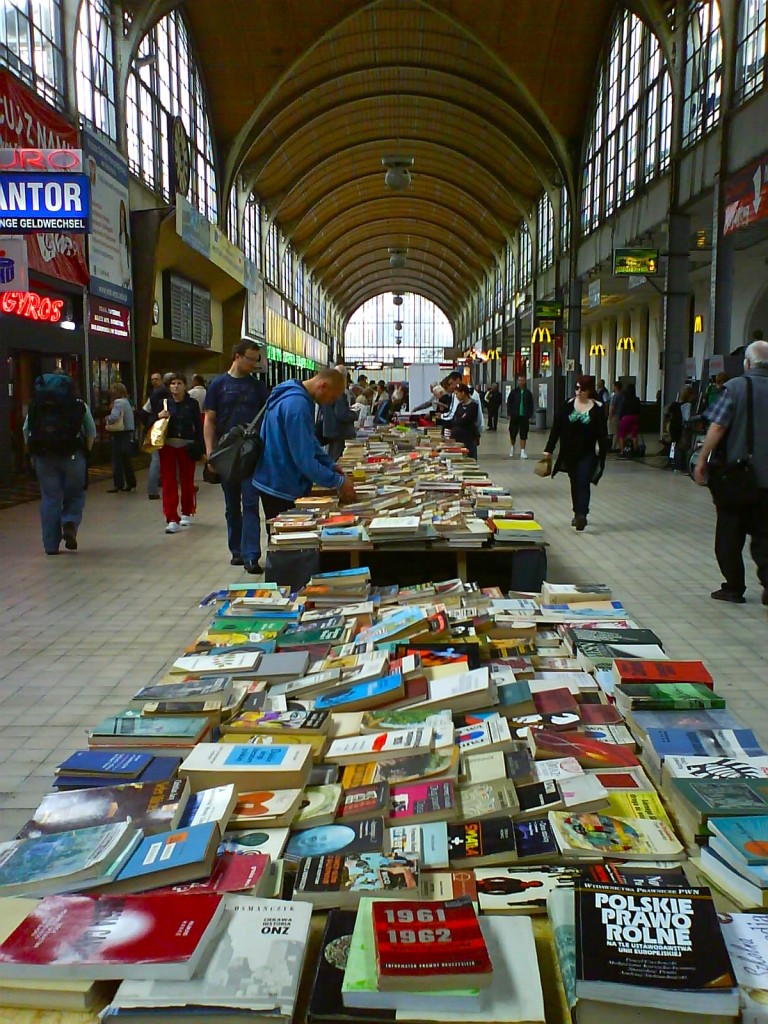

Poland is not difficult to reach, and entering such a different cultural universe in so short a time is dizzying. There’s not just the frisson of a new language, the new signage, the textures of crumbling walls and tatty public spaces, the buzz of chaotic rail stations full of the individualism that comes with comparative poverty, people imprinted with need and making do. There’s also the helpfulness and extroversion that makes you imagine you are farther South than you really are: the old woman on the tram who helps me with the ticket, the chattering girls at the hostel who draw beautiful maps, the louder voices and larger gestures. Then there is the food: it’s easy to lighten things up here with some pierogies, mushroom and sauerkraut, a potato pancake and a glass of excellent Piast beer, or a shot of vodka infused with bison grass.

Why not go a little farther afield than the border, and reach the university city of Wrocław (pronounced Vro-tz-wav) in Silesia, some five hours by direct train from Berlin. Crossing this border gives the historian in me goosebumps. Germans know the city of a half million better as Breslau. In fact, it was a majority German city from the Middle Ages, and part of a united Germany until the end of Second World War. The German population was then expelled and resettled elsewhere in Germany. Poles meanwhile were brought in largely from cities in the East, like L’vov, annexed by the Soviet Union. It is also a region where large numbers of Jews were killed, especially in nearby Auschwitz. By 1950, 75% of the population was new.

These momentous historical events are not easily visible in the landscape, the beautiful woodlands seen from the train. I notice a young man lead a cow from his bicycle. Then the countryside intersects with city, with a grey sprawl, of dispiriting poverty mixed with the new glass of more recent investment, before arriving in the restored historic centre.

Wrocław left me with many impressions––that I actually saw people lining up for confession here, or had a crazy night in a repressed and cagey gay bar that deserves a separate retelling, or had argument with the nationalistic Panorama Raclawicka which casts a Polish defeat as a victory–– but the one that stayed most with me was architectural.

The buildings in the city centre look like those in many cities in today’s Germany. It is very odd to walk around familiar architecture––Prussian and Hapsburg influenced—knowing that these spaces are now inhabited by relative newcomers. But aren’t we all newcomers to the cities the dead have built for us? No, this is not what struck me most.

Wrocław is handsome, with a tremendous ‘Rynek’ or Market Square, surrounded by Gothic and Renaissance palaces. There’s a great sense of permanence in the heavy foundations which fools one into believing that almost everything you see when standing here, in one of Europe’s largest squares, was not recently rebuilt. In fact, the city was 70% destroyed at the end of WW2.

What is mind-bending is that, on one hand, the faithful reconstruction of the pre-war old town is nostalgic. On the other hand, because Wrocław’s inhabitants were almost all new, brought here by population transfers, there is the absence of nostalgia. The pre-war city was not part of their living memories.

What is it like to rebuild a city so impeccably that belonged to the enemy? It is an act of claiming. The city was built, albeit from old plans, for the first time for these people because it was new to memory. To me ––as a visitor who lives in Germany–– the ghosts live on in these rebuilt exteriors. And at the city’s periphery, and corner of one’s eye, are always the drab Communist housing projects which seem superficially the face of post-war Poland. But that would be to suggest that old Wrocław is a German city by right, which of course it is not.

Wrocław has some of the most impressive postwar building anywhere, entirely new to those people who achieved it.

Travel Tips:

Book in advance (at least three days) and try to benefit from a Europa Spezial fare on German railways. Fares to Wrocław are now 29 EUR each way. It’s a pleasant five-hour journey direct. Poland is inexpensive compared to Germany. You can eat in a Milk Bar (lunch cafeteria popular in Communist times) for a couple euros, and sleep cheaply booking on hostelworld.com . On this trip, I took the train Berlin-Wrocław, then returned with a train Berlin-Poznan, spending the day there before taking the evening train, with a second Europa-Spezial ticket, back to Berlin.

One thought on “Poland from Berlin: Wrocław in a Weekend”