Why Germany Welcomes Refugees

What accounts for Germany’s compassionate and generous response to twenty thousand refugees, from Syria and other conflict zones, who flooded across the Austrian and Hungarian borders this weekend? Why is Germany so unlike many of its neighbours in the warmth of its welcome? The scenes of refugees arriving in Munich train station-–welcomed by scores of citizens, then efficiently registered, provided with medical checks, and fed and housed––is probably one of the most heart-warming pieces of news I’ve seen all summer––especially coming from Bavaria, known for its conservatism and tarnished by its Nazi past.

I am particularly impressed because all summer I was down on Germany because of its ungenerous response to the Greek crisis. I couldn’t help but feel different about living in Berlin; I hated being connected to a country with such mean-spirited and stereotyped perceptions of its Southern EU members, and such blind faith in the ideology of austerity. I’ve written about it here and here if you want to read further.

Germany plans to register 800 000 refugees this year and authorised today a six-billion Euro refugee fund. The response from much of the rest of Europe has ranged from disappointing to ghastly, although France and the UK have, I think, been shamed into a more humane response, announcing that they will accept at least tens of thousands in the next two years… which is really a pittance, especially if they have to wait five years.

Meanwhile, the response of countries like Hungary are cringeworthy, with PM Orban saying the refugees are ‘not a European problem, they are a German problem’. Hungarian authorities repelled those seeking asylum with the military, housed those who arrived in camps with horrific conditions, and have invigorated their effort to build a border fence. Meanwhile, the EU has shown itself once again to be deficient in leadership, a talking shop that lacks a unified policy for distributing refugees: the third of a million who have arrived across the Mediterranean to the EU-zone just this year. Britain meanwhile is resisting a proposed quota system where refugees are distributed according to countries’ means to care for them, with UK immigration minister James Brokenshire saying cynically that the UK’s ‘streets are not paved with gold’. Meanwhile, overseas, a country like Canada, with enormous resources and capacity to absorb new immigrants, has accepted only a little over 2000 Syrian refugees, when Germany accepted more than ten times that number just this past weekend.

Why is Germany different?

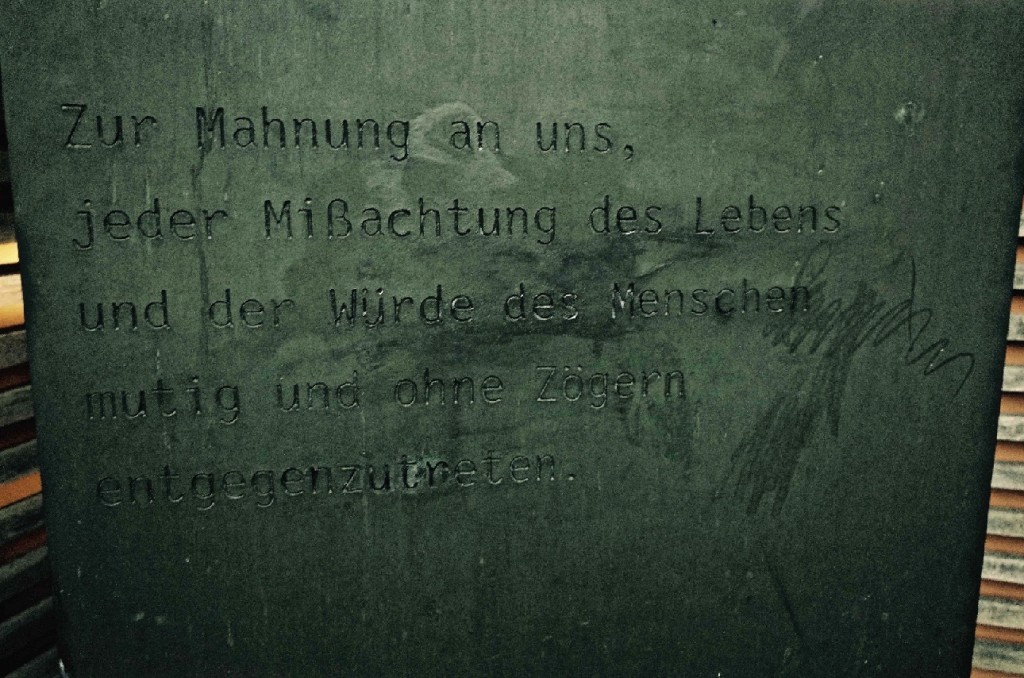

Last weekend, I biked through the old Western neighbourhood of Grunewald, Berlin, where I came across the station’s memorial to the Jewish deportation. From 1941, more than fifty thousand Jews were deported from this station’s platforms to death camps. A plaque here, beneath the late summer trees, reads:

This is a warning that we must oppose, courageously and without hesitation, any disregard for human life and dignity.

I later sat across the street, in a beer garden, sipping my Pilsner, wondering how I should feel, how I should respond, in the shadow of such an atrocity. I think many Germans have thought long and hard about this warning, and years of this kind of moral education (esp. in former West Germany) makes itself visible on weekends like this past one. It is at least a foundation on which to build public engagement and sympathy for the world’s weak.

I cannot help but think too of Primo Levi’s warning, in his preface to his memoire of ‘surviving’ Auschwitz, If This is a Man:

Many people—many nations—can find themselves holding, more or less wittingly, that “every stranger is an enemy.” For the most part this conviction lies deep down like some latent infection; it betrays itself only in random, disconnected acts, and does not lie at the base of a system of reason. But when this does come about, when the unspoken dogma becomes the major premise in a syllogism, then, at the end of the chain, there is the Lager. Here is the product of a conception of the world carried rigorously to its logical conclusion; so long as the conception subsists, the conclusion remains to threaten us. The story of the death camps should be understood by everyone as a sinister alarm-signal.

I am alarmed that across Europe there has been a recent and systematic effort to demonise the other. The ‘stranger’ takes the shape of families fleeing conflicts, who have lost everything, and are looking simply for a place which is safe. In the UK, they are demonised as ‘migrants’, and not even deemed ‘refugees’. It pains me to see the pages of the comments section of broadsheets filled with injunctions against the flood of ‘Muslims’ into Europe. It’s inhumane and prejudiced that countries like Poland, the location of the death camps, or Slovakia only wish to welcome ‘Christian refugees’ (I wonder how this will change given the Pope’s forceful intervention into the refugee debate). Individuals are reduced to a category, a label, to their religion. Because they are deemed less valuable human beings, they are left exposed to the precarity and hardship of overland migration. The mentality of ‘every stranger is an enemy’ is the equivalent to allowing them to perish.

I was lucky enough, after an intensive program studying Arabic, to spend part of the winter of 2008 in Syria, just a few years before the civil war began in 2011. Among the Arabists I know, Syria has always had the reputation (before the war) as the most elegantly old-world country one could visit in the region. Syrians lived beleaguered under an atrocious government, but nonetheless extended a gentle and undemanding hospitality to their visitors. I found Syrians very educated, largely secular or moderate in their beliefs, and incredibly open and willing to debate politics even in dangerous circumstances (in their charmingly soft Shamiya dialect). Next to just how remarkable I found these people, it seems but a side-note to mention the beauty of the country, and the elegant remains from the past there––such the uplifting Umayyad Mosque in Damascus built on an ancient Roman temple. Now, these people, this landscape, and its monuments (such as the former ancient site of Palmyra), are terrorized by a vile and chauvinistic form of religious fundamentalism that has spread from Iraq, born out of conflict exacerbated by Western powers––and meanwhile much of the West closes its doors to its victims.

It must be said that Germany, at least this weekend, has rallied to see these people not as ‘strangers’, and to go beyond stereotypes. In this, there is an implicit recognition of the emergent multicultural nature of the country, and that these people arriving, including so many children, have a contribution to make, given Germany’s low birth rate. There is no doubt an element of pragmatism in welcoming so many often well-educated and determined refugees. Also, Germany has in recent memory the example of what was, for a long time, the failed integration of many arrivals on its Guestworker program. It can now try to do it ‘right’ this time. Nothing like a warm welcome to turn grateful refugees into proud citizens. I am amazed too by the grassroots response in my immigrant neighbourhood in Berlin, by the sophisticated interplay of web-based forums to collect shoes, dictionaries, textbooks, and mobilise those with language skills. Those in Berlin wishing to do more can look here.

The response, of course, has not been universally positive in Germany, and there is a regrettably regional dimension here. Holocaust education was not as rigorous in the former East, where there are very low levels of diversity. It is not surprising to me that it is precisely a former Eastern region like Saxony that has been the hotbed of anti-immigrant attacks and the base of support for intolerant groups such as PEGIDA. That said, it must be said that there are rural and intolerant areas in former West Germany as well, and former East Germany has of course plenty of reasonable people. Yet, it would be a mistake too to ignore the regional trend of neo-Nazi attacks on refugees, such as in Heidenau. And I am not surprised that many immigrants now arriving in Germany are worried that they might be sent there.

I think the differing responses to the refugee question in Europe must too give us some pause. Germany once again is pushed into the position of leading Europe, when the EU and its flunkies in Brussels cannot steer the boat. I think we can anticipate that, with so many countries objecting to refugee arrivals, that the free and open borders of Schengen are in trouble. I am worried that so much ‘the stranger is an enemy’ rhetoric across Europe shows a growing divide between reasonable places and those which are increasingly extremist––and that tension could rip the Union apart. Britain might well be the first to leave, although there are upcoming elections in France. I understand that Germany’s wealth makes it easier for it to extend aid to refugees, but there is no excuse for many others.

Finally, something else worries me, but also encourages me, which might explain why there was such a vigorous response from Germany. This is just a theory, but I am regularly confronted by an, at times, intransigent moral vein running through German public discussion. It was the same one which nastily castigated Greeks for their ‘overspending’ (sadly turning questions of macroeconomics into a morality tale of household finances). The same moral outrage responds equally vigorously, but positively, to those fleeing conflict. Those who are in need because of circumstances which are clearly not their fault are, thank goodness, beneficiaries (and notice that Schuld, or fault, in German also means ‘debt’ and ‘guilt’).

Nonetheless, I know that there is a great deal of kindness pouring out of Germany these days––and that might well just relegate its old reputation, as a land of state-sponsored mass murder, further to the distant past––as it shows just how much it has learned from its mistakes.

—-

by Joseph PEARSON

*This is the first in a series of articles on The Needle about the refugee arrivals in Berlin. Read the others:

2. Razor Wire and Refugees: What’s Happening Now in Berlin.

3. How Long Will Germany Welcome Refugees?

4. Berlin’s Appalling Conditions at Refugee Registration Centre LaGeSo.