You Are Not A Citizen: Berlin’s Zones of Exclusion

A new exhibition opened tonight (1/11/13) at the Kunstquartier Bethanien called ‘In Search of Europe? Equals in an Unequal World’. It is the product of research from Berlin’s Centre for the Modern Orient (ZMO, Zentrum Moderner Orient––I didn’t think people used the term ‘Orient’ anymore, I feel like I’m in a David Lean film!)

The exhibit considers the extent to which Europe is a benchmark against which other parts of the world measure themselves––again, not a question that haunts me at night, given the Euro crisis, and the rise of China and the other BRICS states. Like so many such exhibits, the theoretical considerations take centre stage and the art is happenstance, despite some gentle self-parody from the curators about being pickled in the discourse of post-Saidean Orientalism. The walls are covered with plenty of text, and content analysis would show the impressive recurrence of the words “The Other”, “Performance”, and “Space”.

Yawn. Is it that I’m a historian? Well, shoot me. Or is it just that it’s all so old-hat?

Karem Ibrahim’s installation, ‘Randomly Selected’, however, is a visceral and effective performance piece. As an Egyptian living in Britain, he was inspired by frequent experiences of racial profiling, especially being taken for secondary inspection at national borders in airports despite holding British citizenship. His work can be compared broadly to the Bosnian artist Sejla Kameric’s 2000 installation in Ljubljana which absurdly divided bridge traffic into ‘EU Citizens’ and ‘Others’ (pictured below).

In Ibrahim’s piece, a guard barks at you not to step on yellow lines to one side of the hallway when you enter the gallery. Directed to the right, some visitors are allowed to pass through to the exhibit, but others are ‘randomly selected’ (in this case, the selection does seem by chance, something quite different from what many Arabs and others passing through borders actually experience). Following a winding corridor, you are made to wait. Once admitted into the examination chamber, your photograph is taken and you are issued a visa card (pictured above), something of a souvenir. The actual picture-taking is more pleasant than what you normally experience at a border, but being forced to wait is not, especially if confused friends expect you on the other side (one guy, impatient, simply forced his way through––try that in an airport!)

But it is the evocation of real situations you might have had at borders which makes the installation effective. The narrow waiting space is suggestive of those that exist in thousands of customs areas all around the world, where so many individuals are experiencing moments of terror this very moment.

The German press has been filled with reports on the subject of ‘border terror’ recently, specifically about how American border authorities use personal information farmed from the internet to deny entry to presumably harmless foreign citizens (this from a Dutch writer; this one in German about a young man who made the mistake of entering the US with a guitar; and this one about a German writer subject to a travel ban). The installation in this way responds very much to the journalistic Zeitgeist in Berlin, where, of course, news of Snowden and the surveillance of Merkel’s mobile phone dominate.

Now, related: earlier in the day, I was walking down the Maybachufer and was drawn to two public-action publicity stands: one for the referendum on Berlin’s power which will happen on 3 November, and a second petitioning to stop mass commercial and residential developments planned for the former Tempelhof airfield.

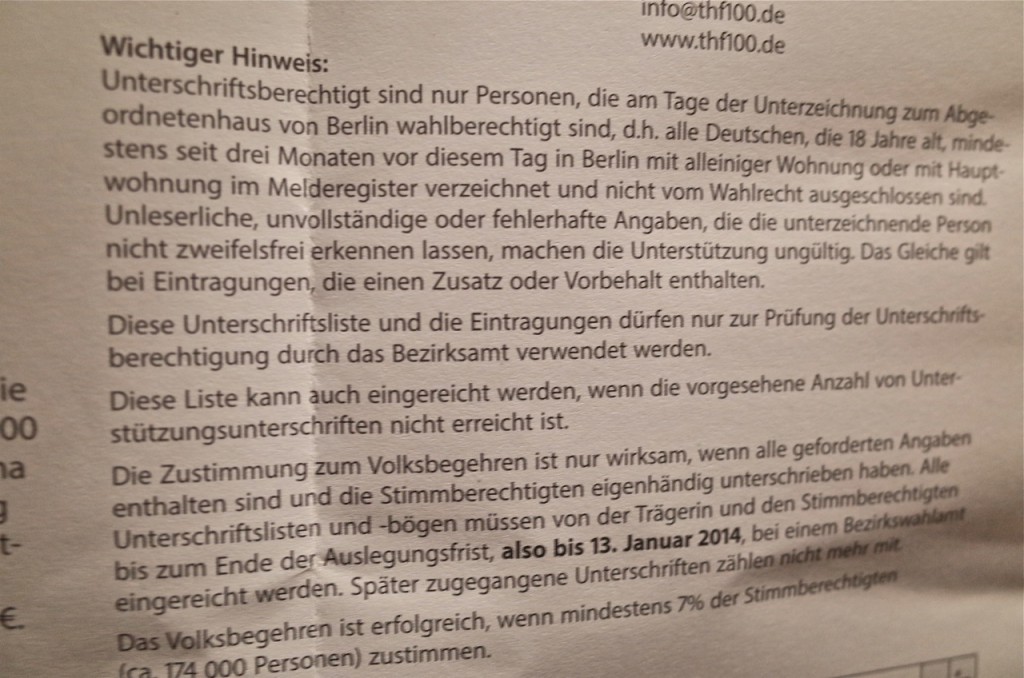

I was all ready to get on board with both causes––ones which affect me as a Berlin tax-payer and resident who pays a power bill and goes to Tempelhof a couple times a week––but of course I am excluded from this kind of decision making because I am not a citizen. I called up the Burgeramt about participating in the referendum (after all, EU citizens can vote for the Berlin mayor), and got a ‘Nein!’ before the phone was hung up. The materials for the petition (pictured below) make quite clear that long-term non-German Berliners cannot have a voice. So much for civic participation.

All this seems hardly cause for complaint when compared to the struggles of all those asylum seekers still tenting for at least another two weeks in the cold of Berlins’ city-centre refugee camp on Oranienplatz (you can read about them here). You hardly need to visit a mock-up border control in an arts space to understand what exclusion means in the German capital.