How We Were Chased out of Görlitz: Wes Anderson Meets Reality

I must admit that the idea of spending the weekend in Görlitz came up after watching the film, Grand Budapest Hotel, filmed in the south-eastern German town just 200 km south of Berlin. The foyer of the said hotel is the atrium of a department store, built in 1913. It is a survivor of two world wars, the rise and fall of the Nazis, Communist East Germany, and the recent years of economic crisis. In the film, the Grand Budapest is a whimsical and stylized hub of international personalities, art thieves, leaders of occupying armies, and the refuge of anti-fascists and illegal immigrants. In Görlitz, the department store is abandoned.

We decided to stay in the same hotel where Wes Anderson’s film crew set up shop, the elegant Hotel Börse, in the baroque money exchange on the main square. We could not believe how stunning this little town is: a jewel. Arriving late after-hours, because of a long delay in a traffic jam on the Autobahn, we were charmed as the hotel porter rolled up on his bike with the keys. He had not asked for a deposit of any kind, and we were touched by the small-town trust and kindness. With our car in the Untermarkt, surrounded by Renaissance houses, and cobbles, we felt, in our skinny jeans and the pulse of electronic music still on our radio, like we’d arrived from the wrong century.

For Görlitz is a place apart. After World War Two, Germany to the East of the Oder-Neisse rivers was given to Poland, with the resulting expulsion of up to 14 million Germans, or Vertriebene. Our group of Berliners found it difficult to adjust to the dialect, which we had never heard before. To me, it seemed slurred with wide vowels. We soon realized that we are in the largest town left in Germany where you can still hear the dialect of what is otherwise a vanished land. Görlitz is the last remaining large settlement of Silesia, since it is located west of the rivers, in Upper Lusatia. There is even a Silesian Museum here.

Not only is Görlitz (pop. 50 000) a cultural remainder, absorbed into Saxony, it is also one of Europe’s divided towns, and used to span both sides of the river. The bridges were blown up during World War Two, separating it from what became the Polish town of Zgorzelec (pop. 30 000) on the other side. It was only in 2003 that the old-town bridge was rebuilt. Since 2007, with the Schengen agreements, uncontrolled movement between the two sides resumed.

The town is deserted on a Friday night; we can hear our feet echo from the cobbles. We are overwhelmed by the age of the place. Görlitz was one of the few historic centres in Germany spared during the Second World War. The concentration of undamaged buildings is such a contrast to the either tawdry or too-perfected confections of reconstruction elsewhere. Here, time has warped the stairwells, softened the cobblestones, given an organic bent to the shape of the 16th-century houses. We enter the Obermarkt where we pass the open door of an old building, beyond which we see what looks like an exhibition space, with antiques, a workshop, tools, chairs in rows as if for a concert, and we decide to walk in.

There are voices from behind a curtain, partly open, and when we pull it back, the assembled company, crowded around an old wooden table in candlelight, to the heat of an ancient wood furnace, look at us curiously. I ask if it is a museum, and they reply that it is a private residence. We are self-conscious that we have trespassed, but we are very kindly asked to join them, and the owner shows us around what was once the old brewery, up the solid stone stairwell, and then on to the deteriorating floors above, where in places you can see down several stories, where the beams are exposed and the floors sagging. It reminds me of 90s spaces in Berlin that you simply can’t find anymore. Each step feels dangerous, so I stop where I am and strum up a conversation with a young man named Andreas who was at the table downstairs.

He has bright eyes and lives in a left-wing collective housing project on H…straße. There’s going to be a brunch on Sunday, then a flea market. ‘You should come’, he says. Then he describes how their home is regularly attacked by neo-Nazis who throw bottles at it, and beat up their lefty friends at city festivals or when they’re walking at night. On the Polish side of the river, he says, the residents have more initiative and more fun than on the German side, where there mentality is more closed and people stick to ‘their own plates’.

I know a little about these tensions, exploited by the extreme-right NPD party, who in 2005 were allowed to demonstrate in Görlitz’s town square, and in 2009 to put up anti-Polish signs directly on the border (‘Poland invasion stoppen’). The NPD enjoys the greatest popularity of anywhere in Germany in Saxony, having gained 8-12 seats in the regional parliament, and 5.6 to 9.2% of the vote in the last two elections, compared to 1.5% nationwide. In Görlitz, approx. 5% of the vote goes to the far right, feeding off almost 30% unemployment, although most people vote for the CDU or the former Communists, Die Linke.

We all return downstairs, sitting around the wood stove, with the shadows flickering about the roof beams and iron implements, and I am again struck by how this scene could be from the 19th century or from the beginning of the last century. It’s only when one of the local visitors around the table makes a casual anti-Semitic comment that we decide it’s time for us to leave and go to bed.

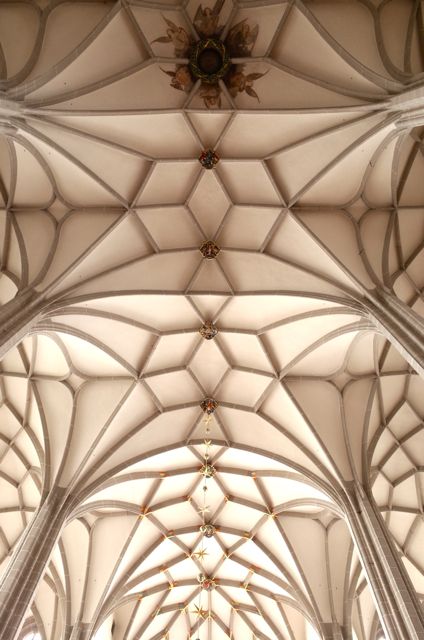

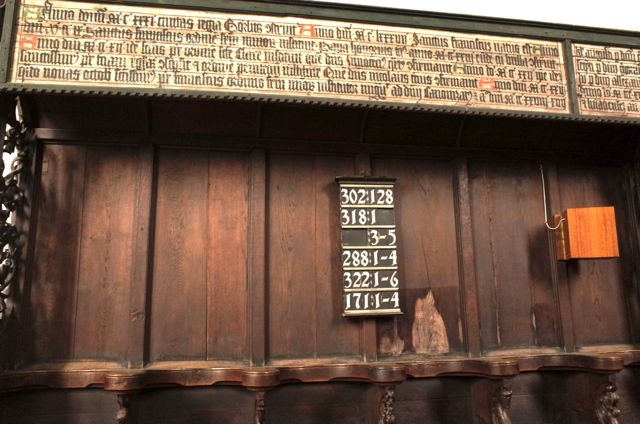

In the morning, we wander again around town, and visit the magnificent 1913 department store, with its glass atrium, used as the hotel lobby in Wes Anderson’s film; it can only be observed, strangely, through a glass door inside a generic Drogerie, decked with bath products, that now occupies the old foyer. The nearby 13th-century Dreifaltigkeitskirche (Holy Trinity) church, has a late Gothic altarpiece, high painted vault, and choir stalls with bold inscriptions.

But it is St. Peter’s church, the Peterskirche, with its Romanesque doorway, adorned with spooky gargoyles hiding beneath the branches of its arch, luminous 15th-century gothic interior, and organ spangled with suns (1703), that forces me to stop, and simply sit in a pew, and just look up. What a beautiful place.

We then slip over to the Polish side, amazed by how easily, and uncontrolledly, one can simply walk between two countries, suddenly aware of the remarkable achievement of European integration. We drink cold Polish lager, and eat hearty pierogies, along the Neisse river looking across to the old German town rising from the opposite bank. Polish Zgorzelec was never the centre of the pre-war old town, and still feels peripheral, with its breezy avenues and Soviet-style blocks hidden behind the waterfront. We buy some Zubrowka vodka in the supermarket for cheap (the brand is the inspiration for Wes Anderson’s republic, its capital in Görlitz) and head back across the river for our disco nap.

You might think we were optimistic to think there is a disco in Görlitz, but there was one, and we will get to that. As the sun went down, we headed back to the Polish side of the river for more grub, and found the atmosphere, after dark, remarkably changed. At the Polish restaurant we laugh loudly around the table in German, order salads, but are then told, around 9:30pm on a Saturday night, with the restaurant still almost full, that the kitchen is now closed. When we pay, we experience a cold shoulder that sets us all speculating as we wander down the riverbank. We enter an underground bar near the bridge, where there’s a long table full of middle-aged German men chugging cheap bear and barking rudely at the lovely waitresses. The drunkards seem like they are going later to a Polish bordello just down the road. The testosterone levels have us scurry back across the river.

On the main square, we enter yet another bar, where there’s a long table, unoccupied except for two seats at one end. We ask if can sit down, and a gruff thug tells us, ‘no’. Another voice says, ‘We’ve heard too much English in here’, and we leave quickly to avoid what feels like an escalating situation.

Later that night, we find ourselves in a nightclub, I think the only such establishment in Görlitz. To the thumping trash electronica, young women sway barefoot on the slippery dance floor covered with broken bottles, guarded by their hulking men, with their buzz-cuts, white t-shirts, jeans and black boots. We dance, huddled in a group, as the whole club gives us a wide berth, observing us curiously, with a clear edge of hostility. In the men’s room, I stumble across the beginning of a fight: one man accusing the other of having taken a peek at his penis at the urinal. When I return to the dance floor, we decide it’s safer to walk back to the hotel all together.

Between these unsettling nocturnal experiences, we end up in a basement bar on the Untermarkt, which was more welcoming, with good electronic music. The locals, yes, stood around the bar, silently, and curiously, watching us stiffly as we danced wildly the whole time, but eventually one of the local men approached us and tentatively began dancing himself. He looked relieved when we asked him if he was from Görlitz.

‘Yes, I’m from here! And I’m so happy to see people with some energy arrive, people who don’t care what people think if they want to dance: it’s an event to have you here’. And here I’m quoting, because all of us were quite aware of the danger of approaching Görlitz with metropolitan snobbery. We did our best, I think, to try to appreciate the place and relativise its Lutheran inhibitions, or Communist-era mentalities that discourage people from sticking out and bringing trouble to themselves. Our friend continued, ‘You know, it’s really exciting for me to speak English. I lived in Australia for eight months. Sometimes you see people on the street who look like they are from somewhere else, maybe working on a film. You can tell by the way they are dressed. And you hope that they might speak English’. His girlfriend joins us, and, when we tell her we are from Berlin, remarks that she has not been there in twelve years.

We were actually surprised to hear how many young people we met (the few, since Görlitz is a retirement hub) have never been to Berlin, or had only been there on shopping trips with their parents as children. Görlitz is not easily reached from the capital. From Berlin, you cannot arrive directly by autobahn, but via a secondary road branching from the small city of Cottbus in Brandenburg through the depopulate plains. Trains (3 hours) from the capital also require a number of changes, usually through Cottbus.

Now, upstairs, I chat with the bar owner in the doorway, as he smokes on the main square. He lived in Berlin for a year, and wanted to open a place here that reminded him of being somewhere else. ‘Except I wanted to be here, I am from here. I know every stone of this town’. He tells me, ‘Berlin is too big’.

I ask him whether he goes to the Polish side, and he replies, ‘No, maybe just for a drink or something cheap to eat. It’s a shame, but we Germans aren’t welcome there. You know, it’s a border mentality’. Our friend downstairs later explains how he was always told, from a young age, that it is dangerous on the Polish side, not to go there, because they will steal your wallet or your car. He repeats those words, ‘it’s a shame’. But, no, he never goes there.

In the morning, the sun finally comes streaming through our windows, we sit out under the glorious facades of the main square eating a good brunch and feeling happy. We bring round the car to pick up our luggage, and leave it where the hotel suggested, in a legal parking space on the main square, near the café. We load up our things, and then one of us wants quickly to visit a shop that sells a dizzying array of mustards. We decide to go and come back in five minutes. We lock the car and have walked 100m when a woman, about 40–years old, whom I noticed also sitting outside at the café, comes running after us to tell us off, that we simply can’t park in the main square all day while we visit the city.

‘I know you are from Berlin’, she says, emotionally, ‘But here in Görlitz, we have some Bewusstsein [conscience]’.

We are all too shocked to know how to reply. Shit, are they going to chase us out of here with pitchforks? It’s only when we get back in the car, and are on our way, that my Wessie Berliner friend, sitting next to me, shakes her head, disconsolate, saying that she’s ‘never felt so rejected’.

What’s wrong with us? Were we disrespectful? Did we dance too much? Were we too loud? Too conspicuous? Did we have too much fun? Another friend in the back pipes up singing, ‘It’s a small world after all’, and we all join in and try to laugh.

The street sign indicates that we have left the city limits, Görlitz with a bar through it, and she puts her foot to the accelerator.

14 thoughts on “How We Were Chased out of Görlitz: Wes Anderson Meets Reality”