The Neglected Fall of the Wall: At Bornholmer Straße

Maybe it’s just a rumour. That you can cross into the West.

Chris Gueffroy’s heard a rumour too, that things had started loosening up. The 21-year old was working as a waiter in the restaurant of Airport Schoenefeld when he heard the border police had stopped firing on people escaping over the wall. He was wrong, and trying to get across the canal between Treptow and Neukölln (on 5 Feb 1989) he was shot through the heart.

But then in November a Politburo member, Günther Schabowski, casually announces at a press conference that the requirement to have a visa to the leave the GDR has been lifted with immediate effect.

You and your friends rush to the wall and hope to be let through. It’s the evening of 9 November 1989, at Bornholmer Straße, the northerly crossing into the West from East Berlin. There is a moment of hesitation. Will the border guards fire? They are outnumbered by the demanding crowd on the Bösebrücke. Phone calls are made. Who will authorise the use of force? No one. Will they let you through?

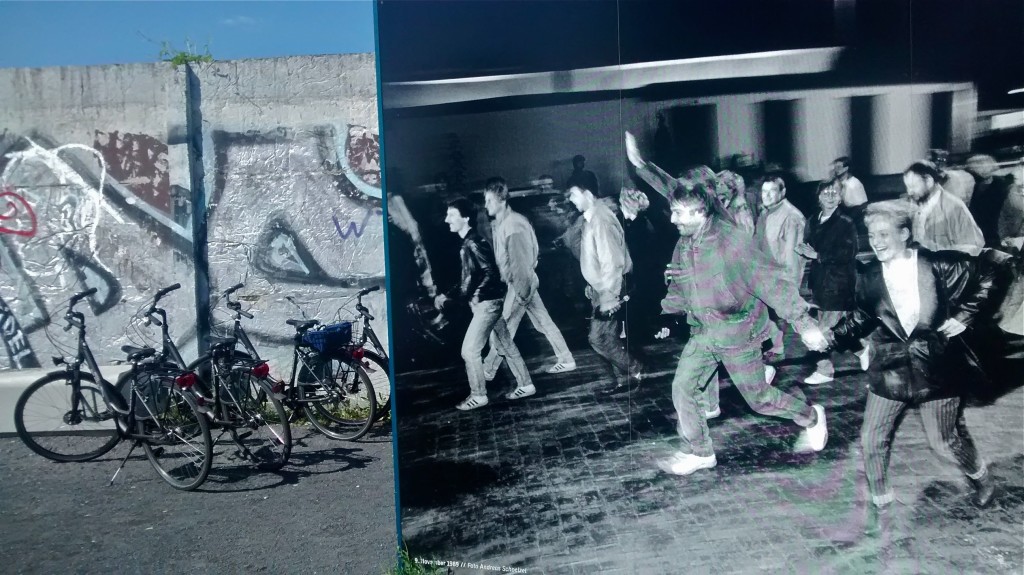

They let you through. You take your first nervous steps forward, but then are pushed along with the crowd, and, soon enough, people are dancing on top of the wall that had separated families. They dance in the death strip, those spaces between the two side of the wall where many, mostly young men, died. At first, the guards try to stamp documents, but there are too many people. 20 000 people crossed the bridge that night without being subject to a border’s control.

The Fall of Berlin Wall first happened here. And yet, it’s not where people come to remember the Wall. Since 2010, there’s been a memorial here, the Platz des 9. November 1989, but most people remember the Wall at the State Memorial on Bernauer Straße or at the private museum at Checkpoint Charlie.

Is it that Bornholmer Straße is too far away from the centre? Or that too little few traces of the original wall still remain here? The border ran along the railroad tracks under the bridge, and we have the low-rise remains of the Hinterlandsicherungsmauer (hinterland wall) and the subtle foundations of a watchtower.

Or is it because the memorial here is recent and consists simply of a few panels with historical photographs and text? Even the City seems to have neglected Bornholmer Straße, the place where those important moments of civic courage happened on 9 November 1989.

Come to Bornholmer Straße today, and the space where the border installation stood has long been cleared away. There are many trees that look about twenty years old. There is the loneliness of the tracks that now pass right over the bridge.

There are empty lots that remind one of the 90s elsewhere in Berlin. We know what awaits these spaces: the kind of dreary redevelopment found elsewhere in Berlin’s former No-Man’s land. Here, it has already occurred with the building of a box store, abutting the bridge, for the downmarket grocery chain Lidl.

A group of cyclists have made it as far as this crossing, as they circle the Mauerweg. They are buffeted by wind, they are confronted by the tawdriness of the place, the inadequacy of the monument.

But then the tram comes squealing down the rails and, instead, of turning into a cul-de-sac as it reaches the border, it continues straight across the bridge.

There seems something miraculous about this, as if there is nothing left to say.