Catastrophe is a Word in Greek

Greece has accepted a tough deal of austerity from European lenders, a “reversal of expectations” (the literal definition of “catastrophe” in Greek) given the results of the “No” referendum.

“Catastrophe” is on the mind of friends here in Berlin, who talk of a coming disaster. The phrase I hear most often is: “Europe is fucked”. I think we have all been made aware in the past weeks of the disunity of the European project, the ineptitude of its leaders, and the fundamental flaws in the common currency––the lack of a cohesive European fiscal policy. We too have been aware of how, in this drama, resurgent local nationalism, also in Germany, spells ill for all of Europe.

Over dinner last night, a friend (a disillusioned ex-investment banker, a veteran of the 2008 meltdown) brought up how little reported in the press the question of “contagion” to other fragile EU economies has been. Let me explain: the markets can absorb a Greek default, in fact they already did so a few years ago. But they cannot withstand Spain, Portugal and Italy following the Greek precedent. Italy would bring everyone down. It is, as the ominous phrase goes, “too big to fail”. The provision of debt relief, a “haircut”, would be equivalently destabilising. This means Greece is required to suffer, as an example to these bigger economies, who have already instituted painful, often failed, austerity measures. This provides the EU with an object lesson of what awaits countries who disobey austerity, or vote for anti-austerity political parties, and it keeps the contagion of Europe’s debt crisis from spreading.

This theory provides a more feasible explanation for why the Germans continue to support a failed policy of austerity. Because otherwise it is extremely puzzling how, despite all the protests of the Nobel Prize winners and the community of international economists, it is possible for the Eurogroup to peddle a medicine whose side-effects, they know, will eventually kill the patient. In the Greek case, it has obviously dried up GDP so there’s no growth to pay back the debt. Even the IMF realises that it is impossible for the most recent bailout to heal Greece, and it strongly criticised the folly of the EU plan this week.

But of course, at the level of domestic politics, austerity is a infuriatingly simplistic story to peddle to voters. Macroeconomics is presented as a home economic morality tale of what happens to those who don’t tighten their belts. We are presented with the busy German ants versus the sun-bathing Greek crickets. The Germans might be brutal, lacking in compassion, inflexible, rule-following, guided by the letter of the law rather than its spirit, and out for their piece of flesh. But the Greeks are spendthrift and corrupt, and lazy, and now getting their just desserts. Obviously, countries do not operate like individuals with their own pocket books.

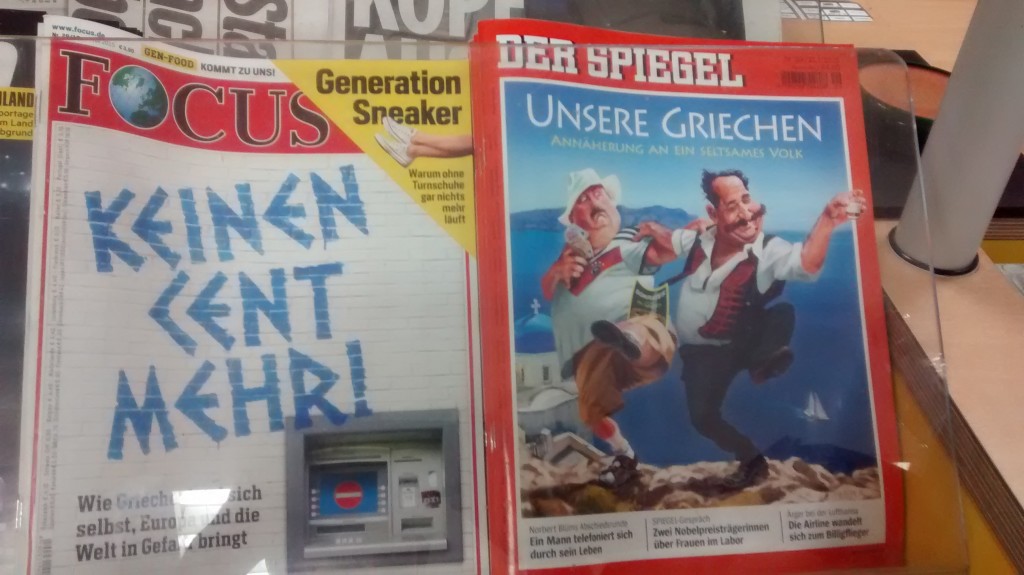

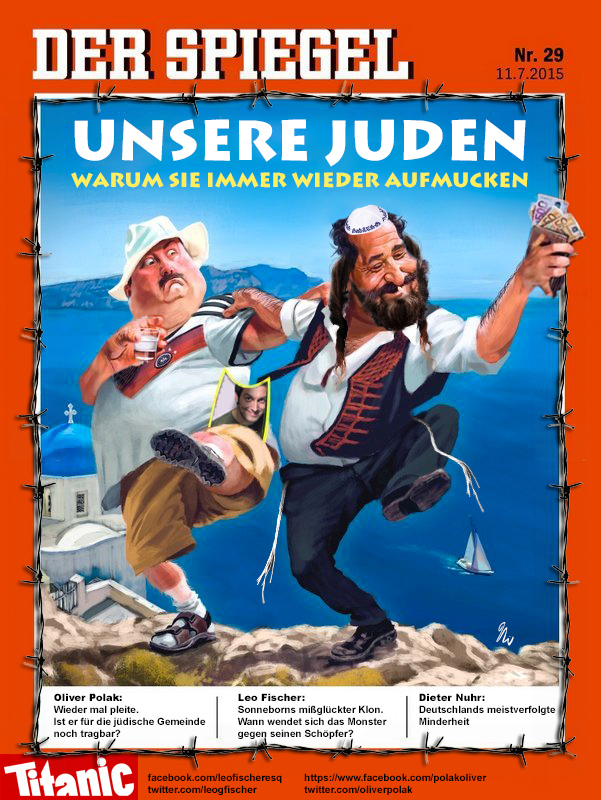

The latter narrative of Greek-baiting has taken a frightening turn in the German press. The cover of a respectable magazine like Spiegel showed gluttonous swarthy Greeks fleecing Germans of money in a grotesque Sirtaki dance. Its caricatures of the Greek people are embarrassing and remind one very much of Jew-baiting in the 1930s, something not lost on the satirical magazine Titanic who did not hesitate to reply with a spoof Spiegel cover where the Greeks are replaced by Jews.

Unreconstructed racial views are an important unacknowledged part of reactions to Greece. Anyone who has lived in Germany is aware of the term “Südlander”, for southern Europeans and Turks. The disappointing stereotyping of these “Southlanders” for dishonesty, shiftiness, and profligacy, is perhaps not obviously racist, because it is directed at fellow Europeans. Nonetheless, closer attention to this racism is explanatory when thinking about the rifts in European solidarity. Meanwhile, it should be remembered that when it comes to money––the gripe in Germany when it comes to baiting either Jews or Greeks––the expense of German unification, which happened on the basis of shared ethnicity, was the subject of some grumbling, but ultimately justified because it was for “one Volk”. This continuity of ethnic nationalism in a country with such a dark past is a worrying sign. Germany may have learned the singular lesson of anti-Semitism better than its neighbours, but it has not applied the more global rule of inter-cultural understanding or even the endorsement of a semi-exclusionary European citizenship.

The rise of scapegoating is an important indicator of how local and regional identification is working at a popular level. National enmities are being unleashed. This nationalism is worrying at a German level, simply because Germany is so big, and powerful, and at the center of Europe––the “German problem” in history that more than one historian has claimed has re-emerged as a frightening continuity after a century with two World Wars.

And how, then, is it possible to embark on a collective solution if the biggest, most powerful, country increasingly is looking after itself? One could make the argument that containing the contagion of Greece is in everyone’s interest, but can you imagine Germany now leading a project of “more Europe”? Because, really, this is the solution: a more unified fiscal policy where debt belongs to everyone, a “United States of Europe”. But in “not a cent more” Germany, and the accompanying atmosphere of castigation, I can not imagine it acceptable to share the debt burden, much less so in times of relative economic hardship across Europe. The project of a common “Europe” has always made its inroads in times of economic prosperity and its citizens retreated to its nationalistic enclaves in times of suffering.

The danger then is both within and without: the retreat to the national community gives room for the far right who erect fences rather than all those bridges we see printed on the Euro notes. Meanwhile, Russia standing outside watching Europe’s dissolution, and is ready to take advantage of the breakdown of collective security. I’m actually surprised that Russia did not jump in to the game and humiliate Europe by providing debt relief to its Orthodox brothers. But, then again, with the low price of oil and other problems on its hands, perhaps it was not able to launch that kind of challenge to Europe’s dwindling credibility.

So where are we today?

Greece was given a Hobson’s choice in their referendum, a snap political event whose absurdity is now being played out as the country accepts a bailout deal much worse than was ever proposed to them in preceding weeks. Tsipras has probably made the mistake of saying “Yes”, even though his people said “No”. Greece will fail in any case, but instead of failing quickly on its own terms, it will now fail slowly at a known cost to German lenders (who in the end hope to come up on top, having benefitted on the whole from low interest payments on their borrowing and a low Euro for exports, even after all the bailouts).

The question now is whether the inhumane sacrifice of Greece, as an example to its neighbours with heavier debt loads, will have been sufficient to stop the spread of contagion. The people who will suffer most in Greece are of course the elderly, and the ill. I like to think there are more compassionate solutions, even in a Europe that lacks the solidarity to fix the broken system. One very telling sign from the Greek talks was the way in which Syriza’s proposal to tax the rich was rejected out of hand by the Eurogroup. As Thomas Piketty has shown us, inequality in Europe comes from how capital has accumulated in the hands of the few. And until it is properly distributed––and there are democratic solutions through taxation to combat inequality––whole countries and families, will have to suffer under governments that have been impoverished so they can no longer offer essential services. I wonder how long those sitting on great wealth can pretend that they are not part of a common system, one that––should the sickness spread from Greece, and it will sooner or later––threatens to bring us all down.

by Joseph PEARSON

****

This post is the second in a series. You can read the first, about Europe’s deficit of compassion, here.

Thanks Joe for an excellent article.