Fear the News Cycle, Not Italy’s Referendum Result

5 DEC 2016

The international press is dangerously over-dramatising the results of the Italian Referendum, after 60% rejected Italian PM Matteo Renzi’s proposal.

Read The Times: ‘Europe in turmoil as Italian PM is defeated’. Or The Guardian’s lead story explaining how Italy is now plunged into ‘political chaos’ after a ‘major victory for anti-establishment and rightwing parties’. It’s a vaffanculo to Europe and the Euro! The New York Times too says Renzi’s resignation will ‘reverberate across a European Union already buffeted by anti-establishment anger’. It’s the third big Brexit / Trump moment of the season! And the Euro is slipping!

Really? This is crazy alarmist reporting and a reality check is needed. And you might just have a better day if you hadn’t been subject to so much misinformation. (If you need first a backgrounder on the referendum, you can read my first post, as an Italian abroad, here.)

The most likely scenario today––after President Mattarella receives Renzi’s resignation––is that Italy will get a caretaker government, led by Renzi’s party, until the 2018 elections. Yes, the face at the top changes, but not the government. This is no Trump coup. Meanwhile, Renzi looks arrogant and dumb for tying this referendum to his political tenure. Then again, his government has lasted longer than all but 4 others since WW2, so by Italian standards that’s not bad.

The comparisons to the Brexit vote are also inaccurate. The ‘No’ vote means that, constitutionally, nothing changes in Italy in terms of how the government functions. People voted for status quo, worried about an over-concentration of power in the House, and as a referendum on Renzi as an unpopular leader. With Brexit, the people voted for a radical change.

In the UK and US, the vote was a cry of anger of the disenfranchised against ruling elites, a cry against globalisation, etc. But none of this is the case in Italy. Rich areas in the North voted against and so did poor areas in the South. Big cities voted against the referendum and so did country people. Urban cosmopolitan people voted against it and so did working people in small towns. People just hate Renzi. Most Italians think Renzi is smug, a Streber (to use the German term for careerist swot), and, with few exceptions, only people in Central Italy (such as his local Tuscany where he’s the golden local boy––that’s why Florence is pictured at the top) voted for him in the majority.

The press is also talking about how this will usher in the populist left-wing movement, the 5 Stars (5 Stelle), and the possibility of a Euro referendum. How? When? If there aren’t elections until 2018? And as the No vote went up in the polls these past weeks, 5 Stelle actually lost support (falling below 30%). The link between 5 Stars support and the No result is not direct. Renzi’s Partito Democratico also has about 30% in the polls. 5 Stelle, however, is unlikely to be able to form a coalition with other parties even if there were elections. In any case, elections are a long way off, and very common in Italy, lots can happen between now and then. As for the Euro slipping on the result, so far it’s been within the range of normal fluctuations––but any single-day fall, however small (as of 7am Berlin time) has been taken as proof, of course, of the common currency’s demise.

*

So what does it mean for today? Renzi is out of a job: he will submit his resignation to President Mattarella who can decide either to accept the resignation, decline it (unlikely), and then decide whether to call new elections. Mattarella is, like Renzi, Partito Democratico, and is unlikely to call elections, with the PD party controlling the House and Senate. He will almost certainly institute instead a caretaker government to rule until the end of what would have been Renzi’s term in 2018. In this case––and we’ll find out later today––again, the Partito Democratico remains in power, but simply with another PM. Keep calm and carry on. Obviously, I’ll think differently about things if Mattarella calls elections later today.

But the bigger question is the following: where does one gets one’s information about European national politics? I think the international papers really capitalised on their readerships’ lack of expertise in the complicated machinery of Italian politics to serve them up a store-bought microwave pizza instead of the real Neapolitan delicacy in this case. Who will know the difference? they think. And if alarmism sells more papers all the better. Even respectable broadsheets need to compete these days with ‘free news’ and ‘fake news’. Meanwhile, correspondents on the ground, working freelance, need to do whatever they can to satisfy their editors’ competitive instincts.

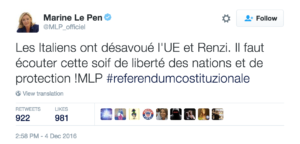

The news cycle is what’s on editors’ minds: how will this story link into past stories and future stories? The ‘story’ in Europe today is populism, Brexit, the effects of Trump, the rise of the far-right, and the European crisis. Every story that comes along needs to play into readers’ confirmation bias and fears. Even if this means betraying what’s happening on the ground. Meanwhile, stories that complicate the news cycle (like the far-right’s defeat in Austria yesterday) are buried.

Shouldn’t our sources of our information be better than this? Why do we consume information from the same people who want to advertise to us? Who want to keep our attention by starting our days, once again, in an alarmist, soul-destroying, way? Why buy from them when there are options?

I don’t think anyone should be getting most of the information on what’s happening in the world from the news, and esp. not via Facebook where there is so much fake news. Not when we can go instead read the bulletins of services that provide specialised information. Instead get the newsletters from think tanks, such as the Council for Foreign Relations, or from very specialised press services (such as playbooks whose audiences are people making decisions: such as Ryan Heath’s Brussels Playbook on Politico), and then when an event happens in a national context, read the national debate using Google Translate if you don’t know the language. The Italian newspapers don’t have much of this alarmism, precisely because their audience obviously knows more about Italian politics. Go there. Please don’t read the Times (be it of London or New York) on Italy. Go to Naples for your pizza.