Why Does Kreuzberg Want to Save an ALDI?

The Kreuzberg gentrification battle continues to rage around the Markthalle 9.

Residents of the traditionally left-wing neighbourhood, paradoxically, are protesting to save a branch of ALDI––a big business discount supermarket with a 50-billion euro turnover.

ALDI sells some of the cheapest food in the industrialised world. As Spiegel reports, “the company has never paid much attention to the consequences of this price spiral — what it means for producers, farmers and for the society at large when low prices become the expected norm”, referring to struggling dairy farmers and cheap products produced in often “inhuman” conditions in Asia.

ALDI is regularly the target of left-wing activism in Kreuzberg. Berlin hosts, every year in January, one of Europe’s largest demos, “Wir Haben Es Satt”, against industrial agriculture. The Markthalle 9 is a centre of their lectures and group activism, and the demo purposefully sets up their information stand each year in front of the ALDI branch.

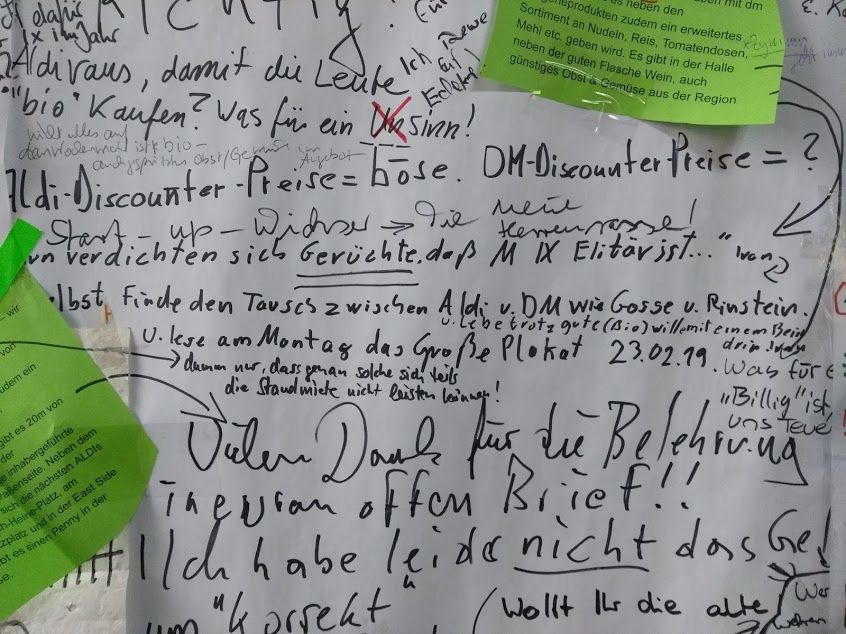

The Markthalle 9 wants to replace ALDI with a DM, a drugstore that also sells dried food-stuffs at low-prices. DM, although being the largest “drugstore” in Germany, is run according to the principles of esoteric Anthroposophy, a spiritual movement founded by social reformers such as Rudolf Steiner. DM’s reputation is for fuzzy spirituality, but also better working conditions and locally-sourced products. They boast corporate and social responsibility, over quick profit. Maybe this is a lot of talk, but it’s definitely a different vision of the world compared to ALDI’s model.

When thinking about the down-side of cheap food for the environment and labour, being against ALDI should be a no-brainer for left-wing activists. And yet, ALDI is now the rallying point of many anti-gentrification activists in the neighbourhood who would like it saved. Why is this happening?

Which supermarket you shop at in Berlin is a class marker, and ALDI is no exception. Penny, Lidl, and ALDI are all working-class institutions, just as organic food shops such as Bio Company are viewed as rich-people’s shops. The sure sign of a neighbourhood’s gentrification is when a Bio Company moves in (and the Markthalle 9 administration was smart enough to choose the more democratic DM instead). The supermarket-as-class-marker works in Germany similarly to the UK, where a Tesco shopping bag might say something different about you than a Waitrose one lying ostentatiously around the house.

The closing of ALDI is therefore a symbol for the closing of an institution of working-class identity. The closure is happening in a neighbourhood which is the epicentre of rising rents or the speculation of big companies like Google. Berlin has the world’s fastest growing property prices, and people living in this kiez which was once one of the poorest neighbourhoods in former-West Berlin have endured much pain as they’ve seen their neighbourhood simultaneously internationalise and gentrify. And it is true that the Markthalle increasingly specialises in expensive foodstuffs––from Truffles to 25 EUR Panettone––not destined for the common man. And as one friend commented, once ALDI closes, there will be no place left in the Market hall where you will be able to buy an affordable pint of milk. The arrival of DM––a place where even rich people like to shop––might be just one more step along towards the ‘end’ of the neighbourhood for its original pre-gentrification residents. In this way, the protest against ALDI really isn’t about ALDI, but the much broader change.

Nonetheless, isn’t it a victory of false consciousness––and a terribly irony––that the poorest members of society have been persuaded that their identity can be represented by a company like ALDI, which fleeces the poor?

It’s also worth mentioning that the Markthalle 9’s was almost ruined by the historic rise of supermarkets like ALDI. So many of the original 19th-century market halls in the city were taken over by mass impersonal supermarkets, such as REWE, who repurposed them, destroying the small businesses that once operated inside. The Markthalle 9 instead was restocked, following a 2009 redevelopment plan, with artisanal and bio stands of the kilometre-zero age. As part of this plan, the remaining big businesses operating out of the market space––a Kik clothing store, the ALDI supermarket––were to be phased out. The announcement that ALDI’s lease to remain in the space was not extended should have been no surprise to anyone.

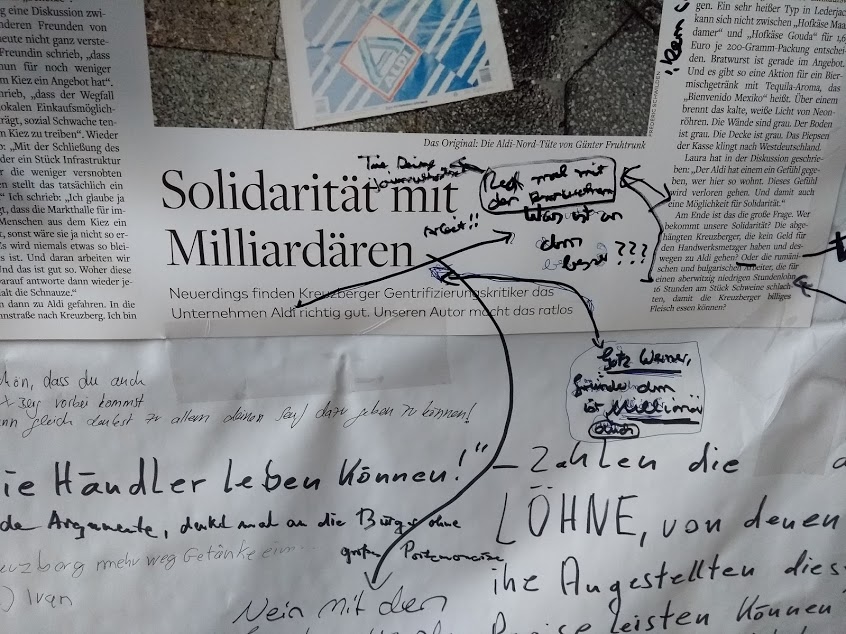

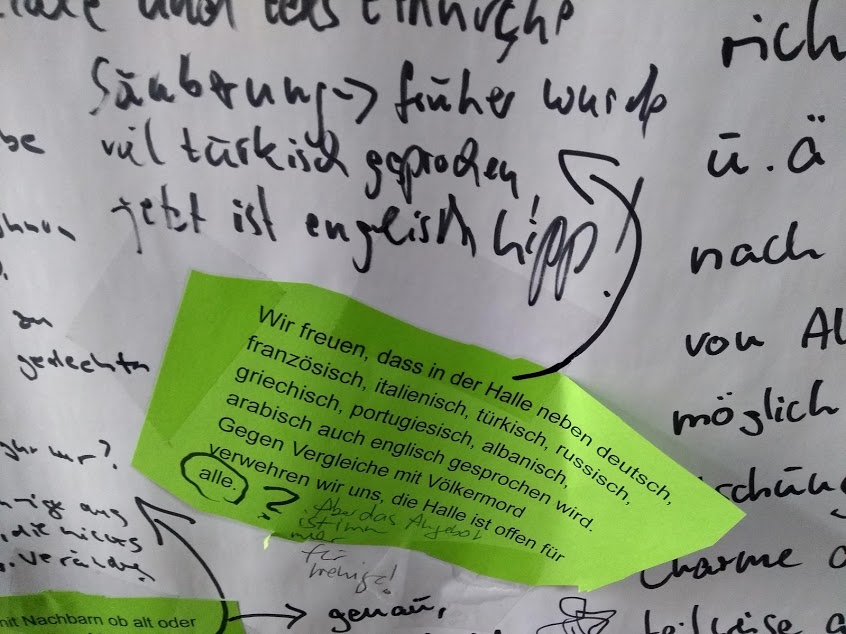

Meanwhile, today, the doors of the old 19th-century market hall, are covered with messages of support for ALDI. The Market hall’s administration have even provided a marker for people to express their grievances, but many of the comments express the “abgehängt”, or left-behind, sentiment of disgruntled populism, and with them comes more than just a whiff of xenophobia.

Other comments simply express the voice of a neighbourhood that is becoming too expensive for most Berliners to afford.

Berlin, 9/03/2019

There are so many false assumptions in this text it’s somewhat mindboggling, but it’s the sing-song of those who just don’t get it. You’d be surprised whom you will find in the ALDI bleibt movement. Journalists, company owners, self-employed devs., shop operators… It’s easy to discredit us as those ‘left behind’. Aside of the fact that ALDI in Germany sells 26% of all organic food in Germany and is by no means the store anymore depicted in the text above, the movement of ALDI bleibt very much represents the current Kreuzberg. A mix of people that are tolerant towards and have respect for each other, if you’re orthodox or not, if you’re left or not, if you have money or not. Kreuzberg in that respect is a future-oriented model of how German society could live together in all its diversity. And it is therefore no surprise that exactly this positive utopia is under attack from those who thrive on segregation, bias, hear-say, those who find it acceptable to exploit people or reducing them to stereotypes, just as this article is a poignant example of. It’s nothing less then a sign of utter disrepect to belittle and look down on those who are dependent to shop at discounters to feed themselves and their family with decent (organic) food (instead of squander a fortune on pseudo/non-organic food as it is often offered at the market stands). To have to do so in the sight of flabby hipsters and overweight squares gluttening on oisters and sherry while parading their bloated stomachs around in too-tight cashmere sweaters is simply repugnant. Not having a clue what people really think of them let’s them come into the M9 – cause if they would, they for sure would abstain.

Hi Andreas, I wish you’d read my article a little more carefully. Nowhere does the article say that people who shop at ALDI are the ‘left behind’ nor does it belittle people in the ALDI-bleibt movement. The comment about the ‘left behind’ referred to the authors of the xenophobic comments posted on the message boards outside the Markthalle 9 (about how there’s been a ‘cleansing’ of the hall, and how they blame the changes on people who speak foreign languages. These are forms of scapegoating and, yesterday, there was even a swastika on the message board). As for your idealisation of ALDI as a company, in the context of a ‘positive utopia under attack’, I’m astonished. How can one say this of a company complicit with illegal logging operations in Indonesia? Or, closer to home, has created deplorable conditions for milk farmers in Germany, who bear the costs of discounters’ cheap dairy products. Where is the solidarity with farmers? Cheap food doesn’t make for a better planet. As for Aldi’s organic products, you might take the advice of Greenpeace who reminds us that “Even if you only buy organic products from Aldi, Lidl, Netto and Co. – every euro that discounters take is also a euro for mass production, forced pricing, and conventional farming”.

Finally, I take issue with your comments that mock people on the basis of being overweight. That’s just mean. I almost didn’t print your comment for this reason. And, by the way, I know one leader of the ALDI-bleibt movement, I don’t belittle her, and she wrote to say she liked my article. It’s because she actually read it. I am dismayed when people write in reacting to what they think an article is about rather than its actual content.

Hello Joseph. Not interested in a feud. ” As for your idealisation of ALDI as a company, in the context of a ‘positive utopia under attack’, I’m astonished.”

If you’d read my comment correctly, you would see that the ‘positive utopia’ clearly refers to Kreuzberg, not ALDI, as I wrote: “Kreuzberg in that respect is a future-oriented model of how German society could live together in all its diversity. And it is therefore no surprise that exactly this positive utopia is under attack ”

So no need for misinterpretation here.

Referring to your (what I find) condescending remarks I would say I stand by my observations. You label people that argue in favor of ALDI as “the “abgehängt”, or left-behind”, in another text segment you find it amusing to call them “the poorest members of society (that) have been persuaded that their identity can be represented by a company like ALDI.” And you marvel about the humane gesture of the “the Market hall’s administration hav(ing) EVEN provided a marker for people to express their grievances”. Oh wow, we, the poorest, the ‘abgehängt’, the left-behind, we’re so thankful for that.

So I think I read and understood your article well. Regarding my weight remarks, think of them as a George-Grosz-style observation.

I admit I would like to see a Grosz-eque caricature frieze set in the M9…

Thanks for your comments.