Bellini or Mantegna?: A Personality Test

“Are you more Bellini or Mantegna?” an Italian friends asks me. Belliniano o Mantegnano?

Not every art exhibit is also a personality test, like this one at Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie showing until the 30th of June.

The exhibition––called the most successful in years, certainly in terms of visitor numbers––is a delightful opportunity to compare the two Italian Renaissance artists. Paintings converse with one another. Almost the same age, related through marriage, and in regular contact, Bellini and Mantegna would often paint the same subjects and consciously imitate one another. Which one you prefer might tell you something not just about the artworks, but also about yourself.

The works of Giovanni Bellini (1430-1516), the official painter of the Doge of Venice, are bathed in that city’s light, the rippling reflections from the sea and the canals. His works are ethereal, soft, emotional. He is not exactly Dionysian––his works are too contemplative––but they certainly do make Mantegna seem Apollonian.

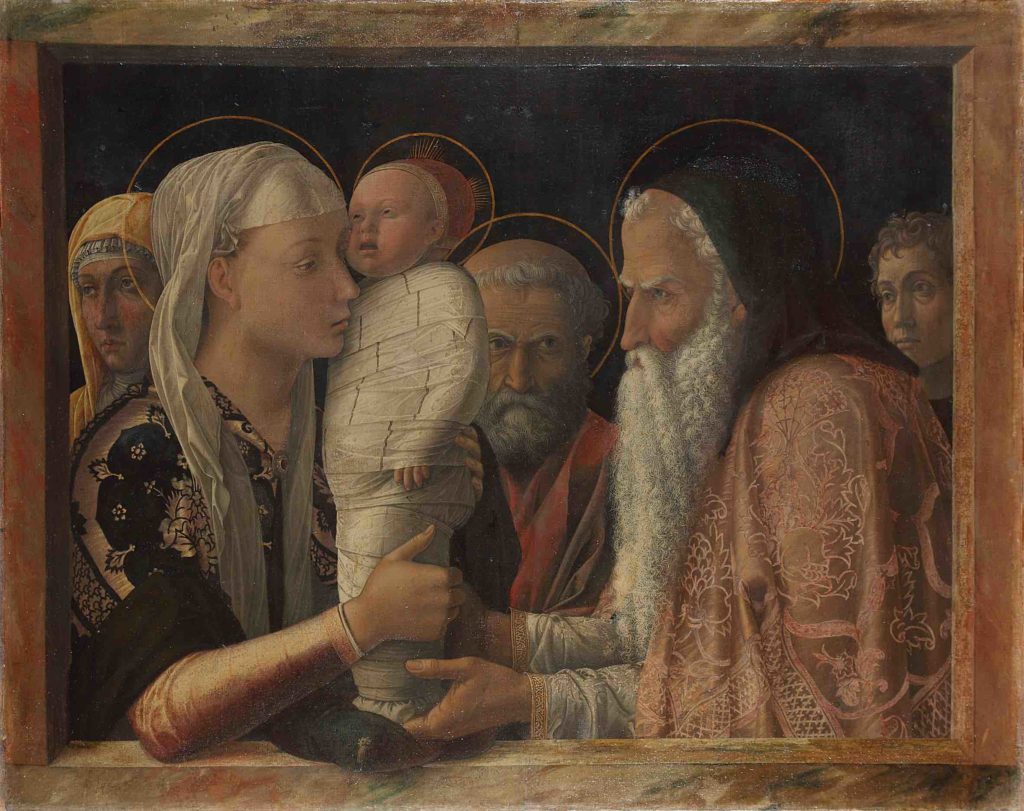

Andrea Mantegna (1431-1506) is inventive with his attention to perspective. More mathematical, his famous foreshortened figures are more exact than his brother-in-law’s. More structured, with clear lines, and bold contours, Mantegna absorbed much of Donatello’s sculptural style.

Nowhere else will you have the opportunity to compare side by side the artists’ versions of the “Presentation in the Temple” (Mantegna, 1453; Bellini, 1472) or the “Agony in the Garden” (Mantegna 1460; Bellini 1465)––paintings by both artists on the same subjects and with exactly, or almost exactly, the same formal elements. Incredibly, this is the first time that an exhibit has been devoted to these deeply connected painters. It could only have happened by bringing together the resources of London’s National Gallery and Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie, two of the premiere collections of both artists’ work (along with those of other institutions).

There are the inevitable voids in this exhibit. I was annoyed, honestly, by the wall texts, which underestimate the museum’s public with their banal explanations: “the human body is the focus of some of Mantegna’s and Bellini’s works” or “the death of Jesus is the central event of Christian religion”. What we really want to know is more about the technique of each painter and arguments to explain their clear differences in style (something you can only find in the exhibit catalogue). By all means, make the show inviting for the general public. Just please don’t talk down to them.

The other real void in this exhibit is the lack of contextualising of the relationship of these two artists in the greater trends of the Italian Renaissance. There is nary a reference to what is happening in Florence (something really necessary if you are going to argue Bellini and Mantegna’s “major role in the development of the sacra conversazione“). And Venice is discussed without reference to the comparisons normally made with Bellini: his followers Titian and Giorgione. One feels a lack of context in this exhibit. Then again, all one needs to do is leave the exhibit for the wings of the Gemäldegalerie to find that context for oneself. It’s just a shame the exhibit doesn’t point the way. No matter: I spent the last hour walking around the Old Masters’ gallery reacquainting myself with one of the Berlin’s greatest museums.

“So, which one are you? Belliniano or Mantegnano?”

“Belliniano“, I tell my friend.

“Me too”, she says.

But then I think how Mantegna was the innovator, and Bellini was usually responding to the other’s work. Bellini’s introspection speaks to me, but I wonder whether I should give more credit to the mathematical spirit of the other.

It’s fortunate we do not need to choose between them.

**