It’s easy to forget that Germany is a new country and that, for much of its history, the term ‘German’ was a loose term, easily malleable for political agendas. It was Bismarck himself who said in 1864 ‘each person calls German whatever suits him and his party standpoint’. Luminaries such as Goethe and Schiller had already suggested it was ridiculous for individuals to think of themselves as German instead of as Free Thinkers. They recognised the forces of disunity, the radical localisation of power and identity, and even language, that typified the history of their lands.

It’s easy to forget that Germany is a new country and that, for much of its history, the term ‘German’ was a loose term, easily malleable for political agendas. It was Bismarck himself who said in 1864 ‘each person calls German whatever suits him and his party standpoint’. Luminaries such as Goethe and Schiller had already suggested it was ridiculous for individuals to think of themselves as German instead of as Free Thinkers. They recognised the forces of disunity, the radical localisation of power and identity, and even language, that typified the history of their lands.

Goethe and Schiller should have had a little talk with the curators of the German History Museum (Deutsches Historisches Museum). You might be surprised by the map installation called ‘Germany and Europe’ (‘Deutschland und Europa’) that welcomes visitors to the foyer of the Zeughaus. Its title suggests an intensely national argument for Germany’s continuity over the centuries. The map jumps forward in time, from the Roman Empire to the present, illuminating the territory of ‘Germany’ and separating it from ‘Europe’ with a thick territorial line. How odd, since what this line encloses (such as the fragmented Holy Roman Empire) was more often than not a mess of fiefdoms and competing principalities that would never have admitted so much kinship with one another. No, in this museum, ‘Germany’ predates its 1871 unification with a presumed continuity that, since it cannot be entirely political, must be argued on the basis of related languages, bloodlines and cultures.

This profoundly national and mythical story (indeed, the national conceptions of most European countries are myths) sets the tone for the ‘German’ History Museum, at the expense of what could be a more nuanced history of migration of the various peoples who have occupied, in the past, the present territory of the Federal Republic.

What are the consequences then for a museum with a national mandate in a country so conflicted about the consequences of extreme nationalism?

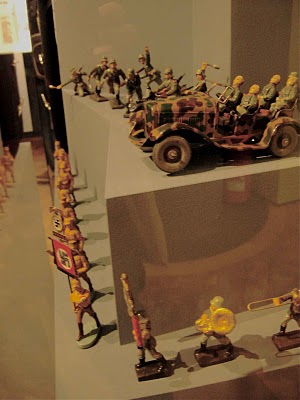

I visited the museum’s controversial exhibit ‘Hitler and the Germans’ (‘Hitler und die Deutschen’), the first in the history of the Federal Republic dedicated to a study of the cult of the Führer. It showcases Nazi artifacts until now kept hidden in the vaults of the museum: children’s toys, board games, uniforms, elaborate weapons with Nazi insignia and banners.

In the case of this exhibit, I am happy to take the definition of the ‘Germans’ as a group tied by blood and race, because that was Hitler’s definition. There is no proleptic argument here, the terms suit the period. We are in the thirties and seeing things their way. Their definition is clearly articulated by the propaganda posters, the pseudo-science explaining hair and eye colour and cranial shape, the flow chart of purity defined by the Nuremberg laws. Charts clearly delineate the difference between them and us, the threat that Jews might soon outnumber Germans (a demographic anxiety that has not disappeared today and recently put forward differently in Mr Sarrazin’s unpalatable book, regarding Muslim populations). The exhibit, of course, distances itself from Nazism’s madness, as does the whole museum, but somehow cannot trace the lasting impact of this national myth-making.

Ultimately, the greatest failing of the exhibit is that it tries to tell a social history about the cult of the leader using the tools of political history. Political machinations are the guiding thread in the narrative, not the groundswell of popular fascism that swept much of Europe in the twenties and thirties. We see a lot of Hitler, but very little of his Germans. Hitler stands behind the disasters of the regime as the source of its evil. We see fascist puppets from a nursery, but learn very little about childhood in the Third Reich. We see a government requisition to a company to provide parts for a gas chamber, and learn about the political decisions to build the camps, but we do not hear the everyday prejudices of working people in that company or ones like it. A panel quotes one would-be assassin of the Führer who believed that by killing the man he would kill the movement. The exhibit rarely argues otherwise, its arguments are history told from the top down.

And so if Nazism really was a consequence of the leader, was Hitler’s death a kind of absolution? I worry that the exhibit can be construed as a ‘feel good’ for those tempted to blame it all on the one man and his political apparatus. Hitler is dead, but I suspect that the mentality of fascism didn’t die completely with him. The Nazi regime fostered plenty of Volksgenossen with their racial notions of belonging. What happened to these nationalists after the war? In what ways was their mindset inherited in contemporary discussion? Are they really gone, those notions of national community that argued the Third Reich to have continuity based on past empires? What of the historical maps where the borders of a Greater Germany expand to contain every place where Germans have lived? What of suggesting that these places are ‘Germany’, on the basis of race, language and blood, before a German state ever existed?

View Larger Map

It’s easy to forget that Germany is a new country and that, for much of its history, the term ‘German’ was a loose term, easily malleable for political agendas. It was Bismarck himself who said in 1864 ‘each person calls German whatever suits him and his party standpoint’. Luminaries such as Goethe and Schiller had already suggested it was ridiculous for individuals to think of themselves as German instead of as Free Thinkers. They recognised the forces of disunity, the radical localisation of power and identity, and even language, that typified the history of their lands.

It’s easy to forget that Germany is a new country and that, for much of its history, the term ‘German’ was a loose term, easily malleable for political agendas. It was Bismarck himself who said in 1864 ‘each person calls German whatever suits him and his party standpoint’. Luminaries such as Goethe and Schiller had already suggested it was ridiculous for individuals to think of themselves as German instead of as Free Thinkers. They recognised the forces of disunity, the radical localisation of power and identity, and even language, that typified the history of their lands.