FEAR and the German Far Right: Conversations with Falk Richter

The far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) is a movement that cannot stand criticism. I got my own taste of their methods this past year, writing for the Schaubühne Theatre in Berlin. Director Falk Richter’s piece, FEAR, provoked the far-right enough that it attempted to have the performance censored in a court of law. The plaintiffs did not succeed: this was not just a victory for a single theatre, but also for freedom of expression in a Europe increasingly threatened by extremism.

Richter’s FEAR plays again this month at the Schaubühne (23-25 / 27 -29 June, with English subtitles on 23 and 24 June 2016) at a time when the world is focused on the question of nationalism in the UK, with the Brexit. I can’t think of a more opportune time to reflect on how the Brexit debate has, in fact, deflected attention away from the Continent’s problems. Fear––of difference, foreigners, cosmopolitanism, multiple identities, multiculturalism, sexualities––has in the news recently been nationalized to the British Isles, instead of being positioned in its pan-European context, with the AfD the most frightening manifestation of such fears in Germany.

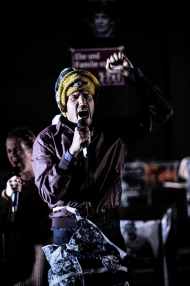

Richter’s piece, FEAR, is what I imagine to be an AfD nightmare––if they only had such bad consciences. I have the hunch that they sleep all too well. Dancers and actors simulate the physical and emotional states of a fearful, hateful body. Video and photos are simultaneously projected, of the main actors of right-wing movements in Germany and Europe. These protagonists represent not only the AfD, but also radical fringes of mainstream parties, such as the CSU/CDU. The performers, meanwhile, provide a counterpoint, in that they come from different cultural, racial, sexual, queer backgrounds. In Richter’s words, they represent ‘the new Germany––the Germany that the populists from the far-right decry and see as evil, as a destruction of “our” culture’.

As the show progresses, Richter’s FEAR is increasingly populated by zombies and monsters––metaphors for the undead quality of the AfD’s political arguments. ‘They are political positions rising up from the graves of the past’, says Richter, ‘We thought they had been long buried, back in 1945, but now they are back’. (À propos, if you haven’t seen Neo Magazine’s retort to right-wing movements, featuring bodies rising from the grave, do take a look at this unusual German viral phenomenon).

In FEAR, Beatrix von Storch, AfD Member of the European Parliament, is tormented by the ghost of her grandfather, who was a minister in Hitler’s government. The fundamentalist Christian, Hedwig von Beverfoerde––whose ‘Demo für alle’, a German version of ‘La Manif pour tous’, holds homophobic rallies in Stuttgart––is likewise lampooned. Neither were, you can imagine, particularly happy with their on-stage depictions and, together, they successfully obtained a preliminary injunction against the theatre.

If you aren’t aware of the details of the November court case involving the Schaubühne, allow me to recapitulate. The plaintiffs claimed their constitutional rights had been violated, and asked that their images not be used in the piece. Performances of FEAR were, meanwhile, interrupted by hecklers, such as by AfD Spokesperson, Christian Lüth. Richter, reflecting on the case, said to me, ‘The two ladies who went to court against my piece had not seen the play nor read the text. Nor had their lawyers. But they wanted to censor it. They are members of the German nobility: Baroness Beatrix von Storch––born the Duchess of Oldenburg––and Hedwig Freifrau von Beverfoerde. This is an interesting detail, in so far that the German nobility has always tried to censor German writers. Their goal was that my play would not be shown at all, or at least not in its original version. They wanted their names and their photos erased from it. They had been very active––via the internet––prior to the court case, organizing petitions against my play. They made plenty of false accusation against me personally and the piece. The Schaubühne and I were bombarded with hate mail and letters urging us to stop the play’.

Ultimately, the far-right’s case was not successful: in December, the court ruled in favour of the theatre, lifting the injunctions against the images’ use. In the judge’s words: ‘any audience member can recognize that this is just a play’. But I think the real meaning of the trial was expressed by Schaubühne’s artistic director, Thomas Ostermeier, who commented, ‘We cannot tolerate attacks on artistic freedom… this is a matter of defending the highest principles’. The atmosphere in the theatre was certainly electric when the decision came down, with the strong feeling that justice had been served.

As Richter told me in an interview, ‘The court battle itself turned out to be really rational and calm. We could prove that the accusations were either false, or that as an artist you actually have the right to talk about politics and political activists––that you are actually allowed to criticize politicians and their political agenda, and that you are allowed to do so through irony, humour and satire. I think the ladies simply were not aware that democratic societies allow that kind of art’.

Between now and the December court decision, the AfD have gained more support and notoriety, not less. First, came the successes in the March regional elections: the AfD entered 3 State parliaments with between 15 and 24% of the vote. In a poll from last week, they have 14% support nationwide (and two thirds would support leaving the EU). Meanwhile, the news has been playing out over the question of the AfD’s leadership: and, oh, what a choice! On one hand you have AfD vice-chairman Alexander Gauland––a serial traffic offender, for speeding and 54 false parking offences––who embroiled himself in a controversy, in advance of Euro 2016, over Afro-German footballer Jérôme Boateng, stating that he ‘would not like to live next to someone like him’ (that is, a black person). On the other, you have chemist-turned-politician Frauke Petry, who made herself famous in the international press for saying German border guards should be able to shoot at refugees–– meanwhile, she is under investigation for perjury in the Saxon State Assembly. The AfD is now assessing its image problem, managing AfD deputy Wolfgang Gedeon’s possibly anti-Semitic statements, deciding in private meetings: does he really think ‘The Protocols of the Elders of Zion’ are for real? That the Holocaust can be reduced to ‘certain crimes’? All this internal discussion is likely to give the party the useful opportunity to say that they have rid themselves of extremist elements.

One thing the far-right has done, however, is mobilise and unify its opponents. Falk Richter has been rather stubborn about letting go of the issues that bother him. We met a few weeks back in his neighbourhood of Prenzlauer Berg over a coffee and talked about FEAR, the court case, and the future of Germany and Europe. The following exchange is based on that discussion:

Joseph Pearson: Why did you decide to take on the far-right in Germany? What was the initial motivation?

Falk Richter: The radical right is recently very successful all over Europe. They provide simple populist answers for the difficult challenges of our complex transnational, post-democratic societies: All foreigners out of the country. Close down the borders. Women should have three children and stay home. The illusionary concept of the strong man who takes care of the family and the nation is suddenly coming back. In Germany, we had an incredibly welcoming culture for refugees. So many Germans provided help, time, money, clothes, shelter for refugees. But there were also those who attacked buses or burnt down homes for them. More than 1200 homes of refugees have been attacked in the last 18 months. Left-wing journalists have been attacked and beaten up. The internet is full of racist and homophobic hate speech. We have a growing problem with right-wing radicalism in Germany. And we have a new very loud and aggressive right wing party – the AfD. A bunch of horrible people that say the most outrageous things in public. One of the leaders of the radical right wing German party AfD is the grand-daughter of Hitler’s finance minister. She comes from one of the worst families of war criminals Germany has ever seen, and it is shocking to see how she uses political strategies, techniques and arguments that remind me of the Nazi party in which her grandfather played a major role. It is shocking to see how all this racism, this hate speech, this contempt for any kind of minority and for democracy itself is coming back with the rise of this new proto-fascist party, the AfD.

That was my starting point: Seeing how the German society is divided: On the one hand there is this open, liberal, multi-cultural Germany in which the majority of Germans want to live and then there is this new ugly, hateful, proto-fascist movement that draws on fear, propagates racism and homophobia, and wants closed borders. How might these radically opposing parts of society clash or co-exist in the future? And is there any way to push this right wing populist nonsense out of the public discourse?

JP: Why did FEAR irritate the German far-right so much? What was your experience with performances?

FR: The radical right wing in Germany, like all far right parties, cannot take any criticism. They are very aggressive towards others, but have a very thin skin themselves. They don’t believe in freedom of speech; they are against free expression in the arts. They basically do not support our open democratic society. In my play FEAR, I show how much fundamentalist Christians in Germany are linked to the far right, how different radical groups that mask as “part of the center” collaborate and drift more and more to the extreme violent right. I use a lot of quotes from radicals, and show images of the protagonists of these racist, homophobic and anti-democratic movements, and how they operate, how they are linked to certain news magazines and blogs. They reacted extremely aggressive. It was a reaction that you would expect in countries like Russia, Hungary or Poland, where critical artists are intimidated by the authorities. Or where critical journalists get attacked. In a way, the protagonists of the German far- right act just like Donald Trump at one of his rallies. If he spots somebody who criticizes him, he verbally attacks him and encourages his followers to form a mob, kick him out, and beat the hell out of him.

JP: How does FEAR fall in place in relation to your other recent work, which to my mind is increasingly political in character?

FR: In all my work I am interested in the physical and the psychological state of human beings in Western society. And I am interested in the question how our political and economic system is affecting the way we live, work, move, think, feel and form relationships. FEAR is dealing with the major shifts in our European societies. With the dawn of a new proto-fascist movement––that openly declares the European Union, open borders, a multicultural society, and equality for LGBT people its enemy––I felt like I needed to be more direct this time. More political than usual. German society is shifting. Fascists are coming back. I wanted to react immediately and strongly. In this sense, it is new and different. And it started a new cycle in my way of working. FEAR was the first of a number of works that deal with the cultural and political identity of Europe and the people who live here now on this continent in its post-colonial era.

JP: What can theatre do about the far-right in Germany? What can we do?

FR: Theatre can bring these issues to the attention of the public. It can start a discussion. It can give the audience the possibility to see things from many different angles, to get a multi-layered understanding of the here and now. What are European values actually, for real? What are our values!? This is a major question in my recent works. What are the values of post-colonial Europe? Is everybody tired of the EU? Are we ready to defend our existing democracy against this new fascism? These radical right wings parties all over Europe are a serious threat to our open societies, to democracy, to freedom of speech. We need to understand what it is about them, against which we need to defend ourselves.

Germany is divided at the moment – just shortly before I had to go to court to defend my play, I was having a day out with friends – we were hanging out together, adults and kids. One of my best friends is a Israeli writer/ director who is married to a Palestinian and they raise their child together in Kreuzberg because they feel more secure and safe here in Berlin than they would in Tel Aviv raising an Arab/ Israeli child as mixed-culture couple. Another friend of mine identifies as a straight man, but raises two children with a lesbian women. And then there was me and my partner (who does not have a German passport either, but grew up in Germany and speaks the language perfectly) and we were the ones playing football in the park with all the kids while our other friends were discussing their relationship issues, and the kids loved to play football with us.

And then, imagine, just the next day, I had to go to court and meet the granddaughter of Hitler’s finance minister, who is the vice-chair of a new proto-fascist party, and this radical Christian, who is organizing rallies and uses hate speech against LGBT people. And they wanted to sue me for writing a play, and wanted the play to disappear from the stage, and their followers wanted public funding to be taken away from the Schaubühne.

It was a collision of worlds.

JP: I certainly know which one I’d prefer to live in.

______________________

FEAR plays at the Schaubühne 23-25 / 27-29 June, with English subtitles on 23 and 24 June.