Gerhard Richter was flying to New York on September 11th 2001. His exhibition 40 Years of Painting was opening at MOMA that winter. He never made it to his destination, his plane was diverted to Canada, and he returned to Germany a few days later.

It took the painter a few years to respond to the events which occurred while he was in the air. The seemingly abstract painting is called ‘September’. It is small, easy to walk by, it has modest proportions. The difficulty of deciphering its iconic subject––the two towers at the moment of impact, spilling debris––is perfectly pitched. He forces us to struggle to see what we have seen a thousand times, an invitation perhaps to consider the consequences of the attacks differently as well. This mix of photo-realism turned abstract, with political overtones, and a finesse for understatement, all completed with virtuosic execution, strikes me as quintessentially Richter. And I know I would care for it even if I didn’t know what it is about.

The retrospective of Gerhard Richter’s works in Berlin (also showing in London and Paris) called Panorama is at the Neue Nationalgalerie until 13 May 2012. It covers his development as an artist from 1962 to today, a half century of production, and celebrates his 80th birthday. The exhibit’s name suggests the obsession with perspective, modes of seeing, problems of representation. Yet the exhibition claims a ‘very palpable sense of the singular nature of Gerhard Richter’s work’. While the curators claim to have closed the hermeneutic circle around the artist, the whole neatly taking in all the parts, I see instead a meandering, and porous, engagement in Richter’s work with debates in the art world. As his own commentary, provided in quotations in the audio guide, tells us, he is engaged in dialogue (sometimes disparagingly) with influences as diverse as pop art, constructivism and photo-realism, and self-consciously places himself in opposition to Duchamp, Pollack or even Titian. With this hyperawareness of his milieu, I don’t think his nature can be called ‘singular’.

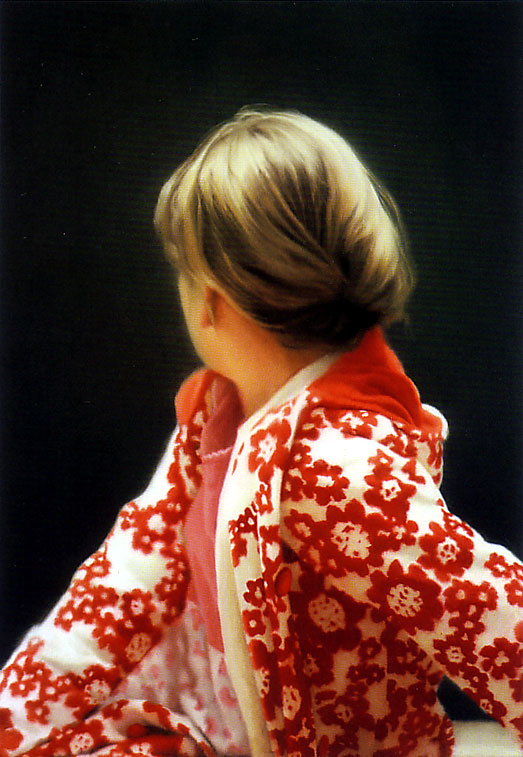

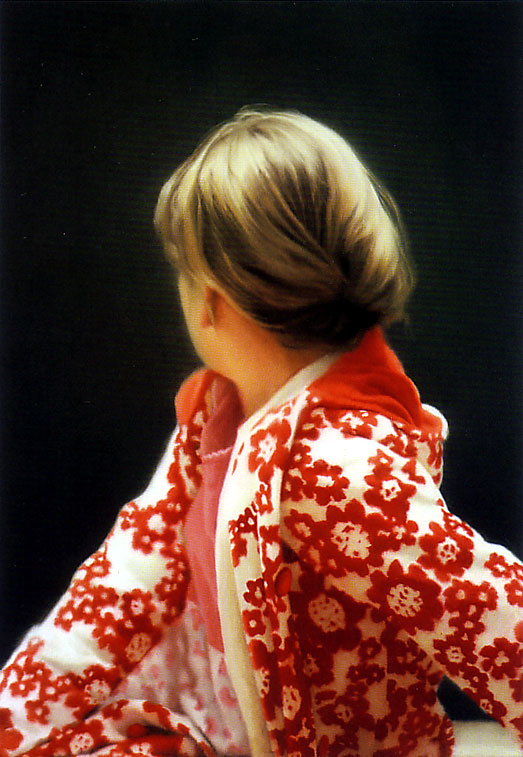

Richter’s reputation is considered sacrosanct by now in the art circles. He is one of the few artists who is given such high-profile retrospectives while still alive (I’m reminded of Louise Bourgeois’ 2008 retrospective at the Pompidou which sealed her place in the contemporary canon). This devotion irks me and I’m tempted to take pot shots at him for this reason alone. But Richter is as alarmingly adept at engaging abstraction as he is representation. A corner of the exhibit alternates between large abstract paintings (most entitled simply ‘abstract painting’) and bijoux photo-realist portraits. One, that teases us with its virtuosity, is entitle Betty (1991) with a delicate rendering of a white and orange flowered cardigan, on which we focus as the subject’s face is hidden.

I heard an old man standing in front of it, saying ‘Wow, he’s good, I thought it was a photograph’. In similar paintings, Richter purposefully blurs his masterpieces, as an invitation to the more jaded viewer to question the authority we give to documetary photographs, and paintings that look like photographs. Richter caters for both tastes in this way: those impressed by skill of reproducing the dominant medium of our age, the digital photograph, in paint, and those that want to have this skill ironised.

This double bid, in building ethos with both audiences, is also transparently a theoretical one. Very much on the surface of his blurring games is a theoretical engagement with the history of representative art and the rise of abstraction in the age of the photograph. It’s hardly necessary for Richter to say so, as he does in his extensive commentary both in the audio guide and in the film

Gerhard Richter Painting. This theoretical awareness is also ostentatiously displayed in his installations of museum glass around the exhibit that both distort and reflect. All this is impressive, but overdetermining and potentially gimmicky. It is also ironic because Richter is so obsessed with chance––it is the basis of his

Cage paintings at the entrance, inspired by the aleatoric music of the eponymous composer, and of the colour palette series that circles the entire exhibit––but very little is left to chance in the photo oeuvres. Perhaps his desire to pull a squeegee or a rake across a canvas, or pick colours by lots for a series, is his escape (his viewers need one too) from the domination of semantic debates and theoretical concerns.

It would be easy to say that Richter is a master who has been mastered by the discussion, or that he is a virtuoso who needs to authorise himself using epistemological theories, or that he should engage in discussion rather than lead it. I did leave the exhibit wondering whether there is not something subservient about Richter’s work, whether the viewer is never allowed to be alone with the pieces without them having to mean something.

But as I sit on the bus home, I do not think about what his works mean. Richter’s paintings stay with me, nonetheless, unaccompanied, without Richter. I wonder: am I longing for a ‘singularity’ in his work, far from the art-crowd chatter? Don’t I need context? What would I do without it in his Sept. 11th paintings? I admire that he tackles contemporary politics. His fascination cannot simply be formal. All this retreats, washed out by the white noise of the bus. All I think about is a group of children playing with one of his installations, waving and dancing in front of their reflections, the brilliant blaze of colour of the canvases behind, the sympathetic symmetry of the Mies van der Rohe building in the deeper background. I think about the abstract painting Forest: leaves in water, disintegrated beyond the point of recognisable shapes, that stain with colour. I think about how the looming and thundering shapes of his cloud paintings dissolve into air. I think about all these formal qualities that change the way I think about painting, and I don’t give a damn if Richter’s intellectual engagements make me, for a fleeting moment, think less of them.

_________

03/2012