Berlin is Still Divided, 25 Years After the Fall of the Wall

In the news, there will be plenty of celebrating the anniversary of the Fall of the Berlin Wall. But for many here in Berlin, not enough time has passed to heal the divisions. Many of my friends abroad ask me: hey Joseph, what do Berliners really think of the 25th anniversary? Today’s post is an insufficient reply to an enormous question. I would nonetheless like to dwell on how (dis)unified Berlin has remained over the past 25 years, and to ask whether the Fall of the Wall is as much of a watershed moment in history as we thought it was.

Let’s start with my Berlin friends, sometimes stoic and slow to share, and how over the past few weeks they have suddenly begun divulging their personal stories. Did F. tell you about his ‘summer of love’ in 1990, when he left Mitte and occupied a distant relative’s flat in the West in SO36 Kreuzberg, and consumed a huge variety of drugs and pornography? Then there’s R. who crossed the border into the East and stood on top of the Wall that first night on 9 November 1989 and had his youth memorialised in photos in the international press. A ‘Wessie’ friend tells me over a glass of Berliner Pilsner how she actually lost contact with her ‘Ossie’ family after the Wall came down, because it wasn’t urgent to visit them anymore. I met a woman yesterday for whom the Fall of the Wall was transformative: one year she thought her little town in the East was the end of the line, the next year she was able to study abroad and travel the world. She never came back. And I know a number of couples whose love spans from East to West, relationships that would have never been possible had the Wall not fallen.

There’s no denying the transformative power of this event on individuals’ lives. Indisputable too is the remarkable change in the East: in terms of infrastructure, services, and changes in professional life, bringing all these to a Western standard. An astonishing 1.5 trillion Euros was spent on this project.

But in more subtle ways, divisions are still very much apparent.

I was at a bar on Yorckstraße last night and talked to the waitress born in 1991, and I asked her whether she feels the Wall is still there in ‘people’s heads’. She replied, ‘No, I feel like a Berlinerin. I’m from the West, but I’ve even started to go to Friedrichshain [in the East] sometimes and, I was surprised, it’s actually pretty cool over there. I know most of my friends don’t think so, but I really think this city has come together’.

I wonder whether she adduced from my facial expression how much I thought her show of solidarity actually reveals the basic problem. 25 years on, Berliners still strongly identify with one side of the city or another, even young people who had no experience of a divided city.

Easterners still go to Müggelsee, Westerners to Schlachtensee or the Wannsee. You won’t often see them at each other’s lakes. I notice my Berlin friends mostly stick to Western or Eastern friendship circles. The Wessies stereotype the East Germans with their ‘fake tans, big dogs, full-body depilation and lack of drive’, and the Ossies to point out how ‘crudely ambitious, label-conscious, materialistic and success-oriented’ their counterparts are. I hate to say that I can spot whether a Berliner is from the former East or West. But I can. Especially if he or she a young person and subject to peer pressure. And I can do it with about 90% accuracy in about 30 seconds flat, and I’m not even German.

Maybe, like all broken relationships, the Berliners need time to adjust to each other’s company again—maybe the same amount of time as when they were separated by the Wall: but that only gives us another three years, and I’m quite convinced we will need more time than that.

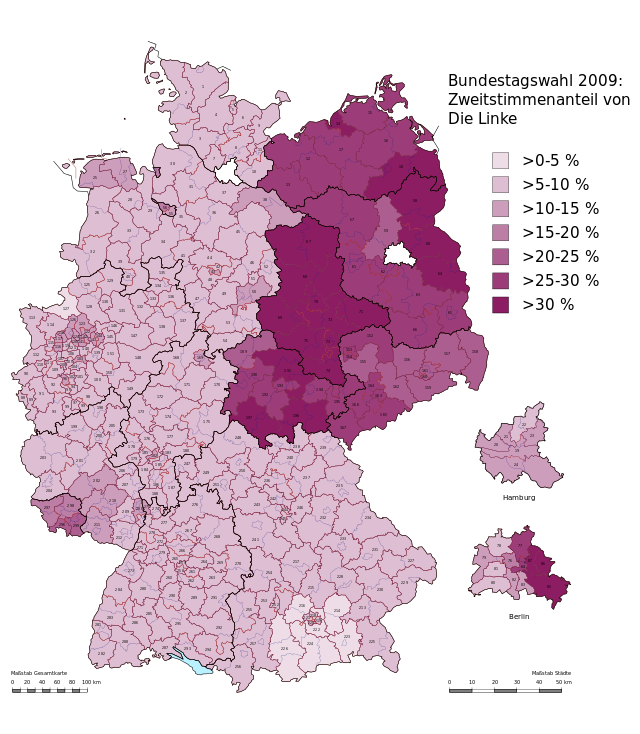

These examples are all atrociously anecdotal, but if you are aching for hard figures, all you need to do is look at the results of the most recent Berlin State Parliament election in 2011 and the Berlin results of the German Federal election in 2013. The successor party to the former East German Communist Party, now called Die Linke, came away with enormous gains in all the former Eastern neighborhoods. In fact, you can see precisely where the Berlin Wall used to be (and the former East German border for that matter), following the edge of the electoral districts that voted Die Linke over other parties. Die Linke campaigns on precisely those securities that disappeared with the Fall of the Wall: guaranteed housing and employment, and welfare benefits. In Thuringia, meanwhile, the Left, led by Bodo Ramelow, is set to lead the regional parliament.

For many in the East, the Fall of the Wall has simply represented the conquest of one system over another. East Berliners have lived under both systems, so they are able to make an abstraction of capitalism and democracy, and think of neither as natural. Unfortunately, despite this perspicacity, the passing of time has brought a certain amount of nostalgia, or Ostalgia if you will. The more unpleasant elements of life in the GDR––mass surveillance, limits on the freedoms of movement and expression––are swept aside in favor of romanticized notions of security, solidarity and community.

(Oops, did I say mass surveillance? I suppose the West doesn’t have the moral prerogative of privacy it once did.)

If the Wall has had a remarkable impact on the stories of individuals, but the city itself remains still quite divided, we are left with a final question of what the story of the Berlin Wall means for history.

My own take is that the celebrations five years ago, for the 20th anniversary, were very triumphalist: world leaders instrumental to the end of the Soviet Union assembled to congratulate one another for the vanquishing of Communism by free-market capitalism. Now, with five years of capitalism in crisis behind us, the atmosphere is not quite so congratulatory. The death strip will be marked by thousand of illuminated balloons––a rather more subtle commemoration than the domino-facsimile Wall of 2009 and the grand political statements.

Meanwhile, the vanquishing of the former superpower to the East is not seen as a fait-accompli either, as President Putin stands arms akimbo at Europe’s doorstep. For many, the greater themes of European history––balance of power, the competing spheres of influence between East and West–––were only coaxed into a temporary slumber by the revolutions symbolized by the Wall’s fall. They were not, of course, resolved.

It is certain that this event has transformed the lives of people who lived through ‘Die Wende’ (or ‘turning point’, as the Germans call the events of 1989 and after). These Berliners had that remarkable experience of being jolted from one political system to another. And we must commemorate the remarkable end of the Soviet system. But the Fall of the Berlin Wall has not changed everything: it has not ‘ended history’, defeated old enemies, or even brought Berliners together the way one expected. As time goes on, and these events are put in the perspective of history’s greater continuities, I believe that we will continue to see a ‘turning point’, but it might not appear as sharp a turn as we originally expected.

-Joseph Pearson

————————————-

Related articles on the Needle:

–The Neglected Berlin Wall Crossing (May 2014)

–The New Berlin Wall Protests (March 2013)

–The Berlin Wall at 50 (August 2011)

–G-Force Mitte (July 2010)