The Railroad Canteen, with no Railroad: Stadtklause

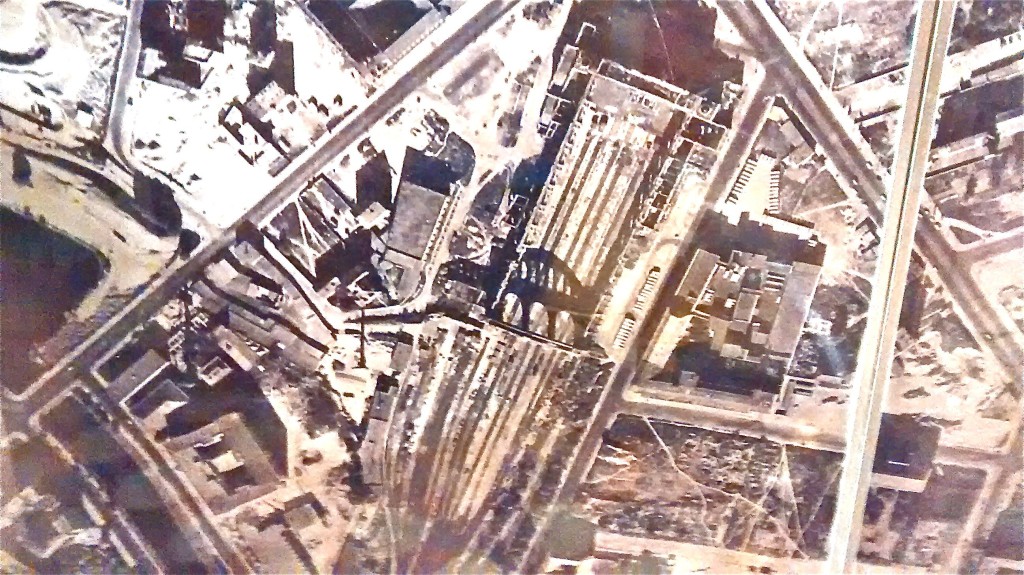

It’s lunch hour at the Stadtklause. The public sit at narrow tables with wooden benches. The walls are covered with antique photographs in places where warped mirrors must once have reflected the travellers. The photos are of what was once the largest rail station in continental Europe: the Anhalter Bahnhof, opened in 1841. And this where you came to have a quick bite before rushing to catch your train to Italy.

Now, the station is a ruin; the remains of the monumental facade face Stresemannstraße. Behind them is a sports field. The surrounding quarter, so close to the tracks, was strategically bombed during the Second World War. There was unfathomable devastation here, also of the Alte Philharmonie, the home of the Berlin Philharmonic. The neighbourhood that has since grown up is breezy, soulless, full of bureaucrats from the nearby ministries during the day, and completely dead at night.

And yet, there are a few surprises.

The railroad company associated with the station acquired the building in Bernburgerstrasse 35 in 1838. It’s just a block from the old station entrance. And, since 1845, with some interruptions, an old Berlin canteen has been located here. The upper floors did not survive, and you can see this from the front facade and the renovated rooms upstairs. But, miraculously, the time-capsule interior on the ground floor survived the bombings. An exhibition space of old photographs of the district is in the basement.

It’s lunch hour at the Stadtklause and the room is full of suited bureaucrats and professionals from nearby Potsdamer Platz, and a couple of clever tourists. The menu is handwritten on a piece of lined paper, and pinned to the wall: there’s potato goulash, meatballs or sausages. Red cabbage, gravy and salted boiled potatoes accompany. The office crowd lines up one by one in front of the canteen window, as is they were in the mensa at work, with trays, and order their food, bring it to their tables and pay later. Everything is homemade (except the sausages), even the farmer’s bread.

Everyone shares tables: there is something workaday, communal and solid about the whole experience. The food is wholesome, bodenständig as the Germans say. Down to earth. I want to say honest, and I try to think about what that human characteristic means for my Knacker. No matter, they sure are tasty. I like the honesty, the trust, that money is exchanged after-the-fact. The prices are ridiculous, 4,50 EUR for a huge plate of home-cooked food in a neighbourhood dominated by the mass production of Vapiano, the nearby malls in Potsdamer Platz and a sprinkling of Michelin-starred affairs.

Here, you look up at all the photographs and feel a thread to the past, to something sensible and proletarian. I think I smell the smoke from the engines, see a woman enter with a leather packing case and flowers picked in Umbria. She’s flirting with a man, covered with soot, who has just cleaned the tracks. There should be a continual rush associated with the excitement of travel across an Old Europe. I almost feel like someone should rush to the front of the line shouting, “I’m going to miss my train”. And then, around 10:30pm, come the elegantly-suited concertgoers, whistling. There are programs on the tables, stained with mustard, and violin cases poised in the corners.

But everyone these days eats around noontime and soon returns to work. By 1:30 pm, all those wooden tables are completely empty. We are left with the nostalgic photographs and the devastation.

I listen hard, for some tremor of that past commotion, but I cannot hear the train whistle.